One of the big stories in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser Saturday morning was that military "brass" updated island officials on how the military would respond to a nuclear attack from North Korea. Military authorities warned there was a "real" threat.

At 8:07 a.m. Saturday, Hawaiian residents saw a terrifying alert message on their phones.

The same alert, with even more terrifying details, broke into a live NBC Sports Network broadcast of a soccer game. The same automated alert interrupted an SEC basketball game being shown in Hawaii.

That alert told viewers to seek "immediate shelter in a building" and "if you are driving, pull safely to the side of the road and seek shelter in a building."

Though it ultimately turned out to be false, many who saw the alert took it to be real, including journalists who were working or vacationing there.

Lorenza Ingram, a CNN producer who is in Hawaii a few days away from her wedding, said as soon as the alert went out via cell phone alerts, she saw people running with their families off the beach. She said she got more information by calling the CNN news desk than she was getting from local officials or the hotel.

WCAU-TV Philadelphia anchor Vai Sikahema, who is vacationing in Hawaii, said he saw the alert on his phone and told his wife he figured they had about 15 minutes before impact. He said he called his children and told them where the family will is, then he said, he called the TV station assignment desk to say if he was still alive in a few minutes, he would be available to report what he saw.

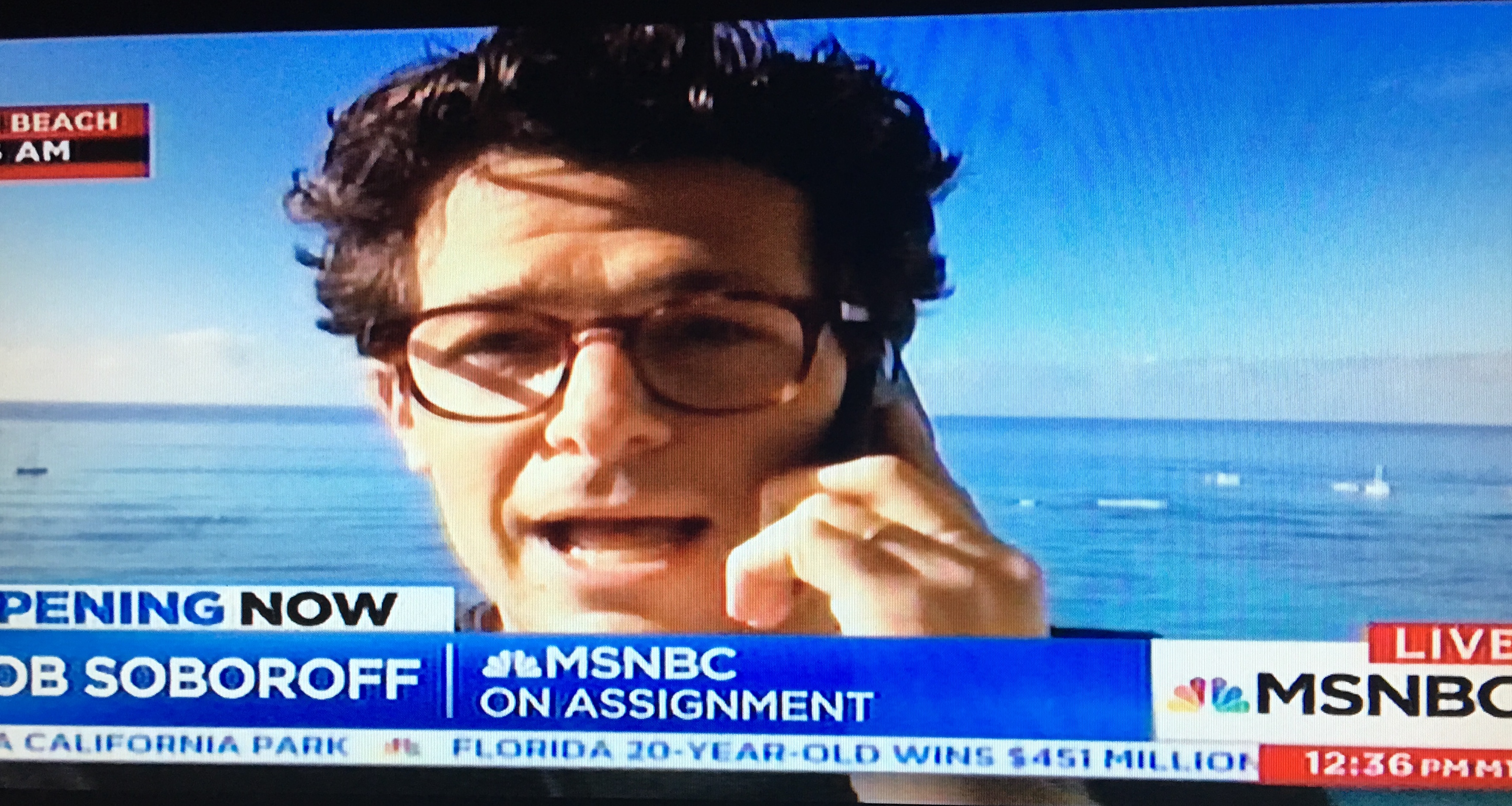

NBC News' Jacob Soboroff reported that he just happened to be in Hawaii right now, on the last day of producing a special report on emergency nuclear response. The NBC journalist is part of the NBC Left Field digital video journalism unit.

Only yesterday, he said, he had been in a Civil Defense command center on assignment. Soboroff said Hawaiians have heard the alarms in test drills before, but he said there were no sirens sounded today.

Soboroff said the state's EMS has staff on duty 24 hours a day inside a command center at Diamond Head Center. He said based on what he heard from Emergency Management officials during his reporting, the time that it would take to confirm a missile was on the way and then alert locals would be a matter of minutes.

Elsewhere, Hawaii News Now collected reactions from tourists and locals who were at a farmer’s market when the alert pinged phones. Local news websites included a video of a man stuffing a child in a manhole.

Without a doubt, this false alarm, and the time that it took to alert the public that it was false, will start an urgent conversation about what role media play in a real alert. Hawaii media reported that the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency website was overwhelmed and unresponsive. Hawaii News Now reported:

Though the error confirmation was sent within about 15 minutes on Twitter, it took emergency management officials nearly 40 minutes to send out a 'false alarm' alert to cell phones — using the same mechanism that sent out the emergency warning in the first place.

A short time after the alert was sent out, authorities from the U.S. Pacific Command in Hawaii sent out a statement confirming that there was no missile threat.

NO missile threat to Hawaii.

— Hawaii EMA (@Hawaii_EMA) January 13, 2018

How emergency alerts should work

This fumble will be an opportunity for journalists to explain the American emergency alert system.

There are a few tiers of the alert system, a wireless alert system that uses cellular devices to deliver messages and a broadcast alert system that affects radio and TV. Because all of these alerts involve airwaves, the Federal Communications Commission will be among the federal agencies that will be asking questions about how the system broke down.

FEMA explains the Wireless Emergency Alerts:

During an emergency, alert and warning officials need to provide the public with life-saving information quickly. Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs), made available through the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS) infrastructure, are just one of the ways public safety officials can quickly and effectively alert and warn the public about serious emergencies.

What you need to know about WEAs:

- WEAs can be sent by state and local public safety officials, the National Weather Service, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and the President of the United States.

- WEAs can be issued for three alert categories: imminent threat, AMBER and presidential.

- WEAs look like text messages, but are designed to get your attention and alert you with a unique sound and vibration, both repeated twice.

- WEAs are no more than 90 characters, and will include the type and time of the alert, any action you should take, as well as the agency issuing the alert.

- WEAs are not affected by network congestion and will not disrupt texts, calls or data sessions that are in progress.

- Mobile users are not charged for receiving WEAs and there is no need to subscribe.

- To ensure your device is WEA-capable, check with your service provider.

The current Emergency Alert System relies heavily on commercial radio stations. This mistaken alert may be an opportunity to ask whether that is still a delivery system that makes sense and whether radio stations, which have consolidated and downsized over the years, even have the capacity to serve such a central role. Here is how the Emergency Alert System is supposed to function on broadcast stations:

- The Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS) is a modernization and integration of the nation's existing and future alert and warning systems, technologies, and infrastructure.

- The Emergency Alert System (EAS) is a national public warning system that requires broadcasters, satellite digital audio service and direct broadcast satellite providers, cable television systems, and wireless cable systems to provide the president with a communications capability to address the American people within 10 minutes during a national emergency.

- EAS may also be used by state and local authorities, in cooperation with the broadcast community, to deliver important emergency information, such as weather information, imminent threats, AMBER alerts, and local incident information targeted to specific areas.

- The president has sole responsibility for determining when the national-level EAS will be activated. FEMA is responsible for national-level EAS tests and exercises.

- EAS is also used when all other means of alerting the public are unavailable, providing an added layer of resiliency to the suite of available emergency communication tools.

The history

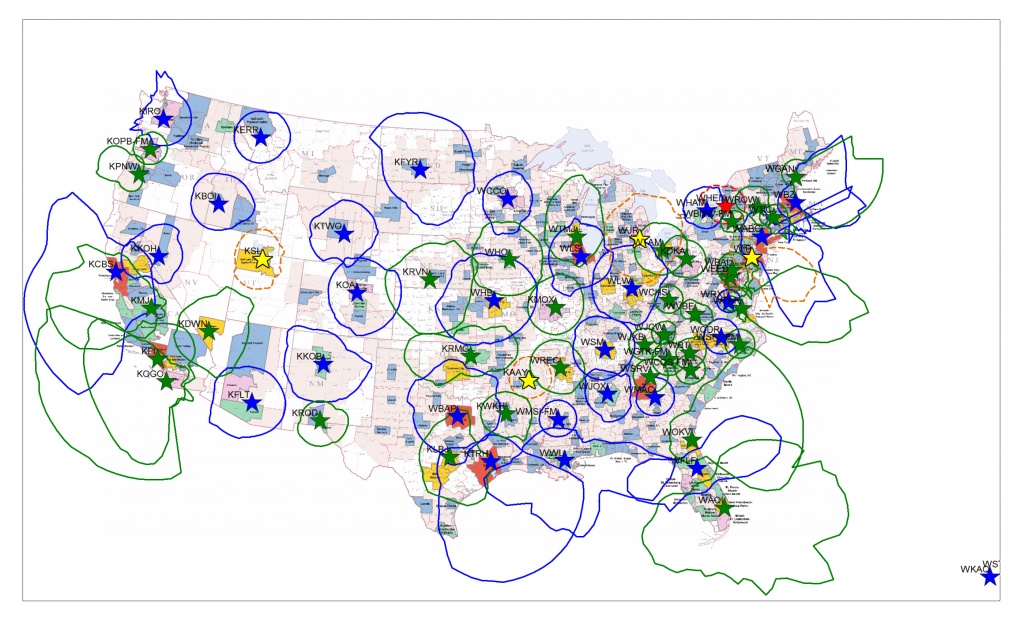

The EAS that we rely on was created in 1994 as an update to an antiquated system that started under President Truman in 1951. The current system is built on the backbone of something called the Primary Entry Point system, which I suspect hardly anybody knows about. It is a collection of privately owned radio stations scattered across the country.

PEP stations, "have a direct connection to FEMA and serve as the primary broadcast source for Presidential National Emergency Alert System (EAS) messages. PEP stations connect to other broadcast stations in order to disseminate messages throughout the country. State and local public safety officials can leverage EAS and FEMA PEP stations when they are not in use for National EAS warning messages."

PEP stations must have backup power generators and, this is key, have the capacity to provide the president of the United States with the capacity to reach the public with a message within 10 minutes. Without a doubt, this mistake in Hawaii will raise questions about whether that system lit up as it should have.

NBC News reported from Ventura County in Southern California where the county is not waiting for the federal government to prepare for a nuclear emergency. "The county's health department launched a campaign starting in 2013 to inform citizens about what to do in a nuclear attack. The county created an 18-page educational pamphlet, four videos and a curriculum for schools and a series of community meetings."

Some readiness experts say Americas are so poorly prepared for an emergency because the government does not want to alarm people by conducting preparedness drills.

The alert error in Hawaii is an opportunity to examine our alert system not just for nuclear alerts but for the range of other threats including bioterrorism attacks and cyber attacks. It is an opportunity for media companies to examine how they responded to this alert and how they would respond next time. It is a great opportunity to talk with your local EMS officials to find out what their protocols are and even to practice a response, which is not something newsrooms do very often, but should.

The Centers for Disease Control planned to meet next week to talk about America's response to a nuclear attack. On Friday, the CDC said the conversation was postponed. In announcing the meeting, the CDC said a couple of weeks ago:

“While a nuclear detonation is unlikely, it would have devastating results and there would be limited time to take critical protection steps. Despite the fear surrounding such an event, planning and preparation can lessen deaths and illness.”

The CDC continued, “Join us for this session of Grand Rounds to learn what public health programs have done on a federal, state and local level to prepare for a nuclear detonation. Learn how planning and preparation efforts for a nuclear detonation are similar and different from other emergency response planning efforts.”