A series of studies sponsored by the Society of Professional Journalists says public information officers (PIOs) are making it more difficult to get access to interviews and information. SPJ is taking its concerns to the Excellence in Journalism national conference and will include a session called “Censorship by PIO: Challenging Gag Orders on News Sources.”

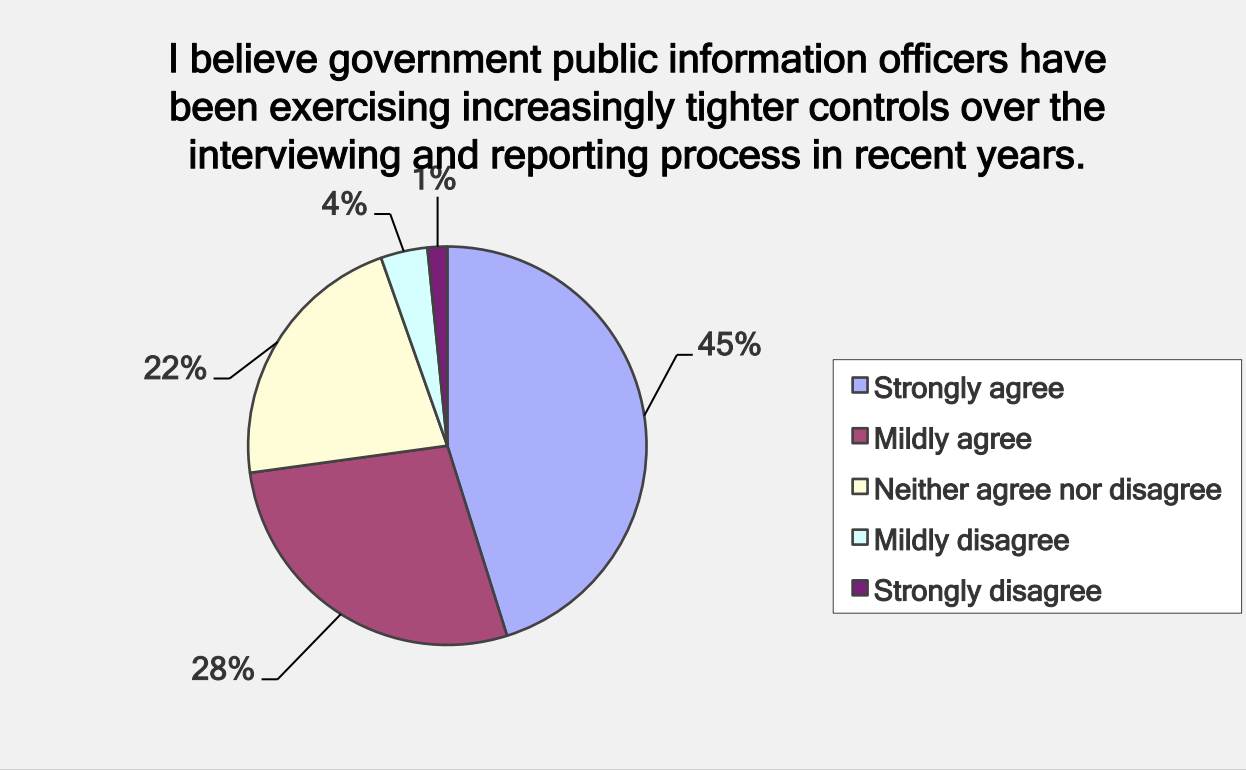

SPJ reports, "Over the last 25 years or so, there has been a relatively rapid trend toward prohibiting staff members from communicating to journalists without reporting to some authority, often public information officers."

The claim is backed up by seven studies conducted by former SPJ president Carolyn Carlson of Kennesaw State University. Carlson is a longtime Associated Press reporter who earned her doctorate while conducting research on how PIOs control information. Carlson surveyed police reporters, police PIOs, science writers, education writers and general assignment reporters. Police reporters, she said, are the most affected group she surveyed. Her survey said, "It is unusual for crime reporters to be able to interview police officers without first going through the police public information office. Almost 60 percent said they could successfully interview officers on their own some of the time or rarely, while 26.1 percent said that never happened."

The Media Relations Handbook, which the authors say is called "the big blue book on Capitol Hill," advises government, associations, non-profits and elected officials:

“It must be made clear to all staff that they should deal with the media only when authorized by the public relations team. Loss of control over communications can be a disaster for an organization, leading to public controversy and loss of credibility. If the communication director is saying one thing to a reporter, and another staff member is saying something different, the reporter will highlight that conflict for all it’s worth."

“Most organizations have policies against talking to reporters, but this is hard to enforce in a large organization. If this occurs and the person responsible makes himself known, it’s best to clamp down as quickly as possible. Usually senior management takes a very dim view of unauthorized contact with the press and will aid in this effort. This isn’t a witch hunt, which, as stated earlier, is usually a failure. This is merely an organization making clear to its staff that there are policies that guide its communication strategies."

It helps when a government agency overtly says it wants to talk to journalists. At NASA, for example, the 1958 Space Act mandates the dissemination of the agency’s scientific findings to the widest possible public. The Union of Concerned Scientists said its survey of journalists found NASA to be among the easiest agencies to cover. On the other hand, the National Cancer Institute's guidelines say "All media inquiries must be directed to the NCI Media Relations Branch."

SPJ ramped up its concern about PIOs having so much influence over news coverage in July 2014 when SPJ, along with 37 other journalism organizations (including IRE, ONA, the Environmental Journalists Association and The Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press) sent a letter to President Barack Obama complaining that PIOs were "requiring questions in writing before interviews, having PIOs monitor and direct interviews with agency employees, prohibiting employees from speaking to journalists and blackballing reporters who question too aggressively."

The first letter changed nothing, so the same groups, this time with a dozen more added to their ranks, fired off another letter in 2015. Now, under President Donald Trump, the same problems with PIOs controlling the flow of information remains entrenched. The news organizations complained again to the Trump administration with the same non-results. In 2017, SPJ adopted a resolution opposing what it called the government's "mandated clearance culture" of requiring journalists to go through PIOs to speak with government workers.

Journalists and police

Journalists tell me that they, increasingly, cannot speak directly with police officers who are on the beat. The SPJ-sponsored survey found, "Access to the chief can be helpful on some stories, but in many stories about specific crimes or incidents, reporters often seek to interview a front-line officer or investigator. However, more than half reported that the PIO actually prevented them from interviewing officers and investigators in a timely manner (33.7 percent some of the time, 18.4 percent most of the time and 4.9 percent all of the time.)

A third of the journalists reported that when they asked officials why they were being blocked from talking to officers, they were told that it was "simply departmental policy" that only top department officials or the PIO could provide interviews. It is especially true, the survey found, at crime scenes, when more than half of the journalists questioned said they rarely or never are allowed to talk with detectives or officers.

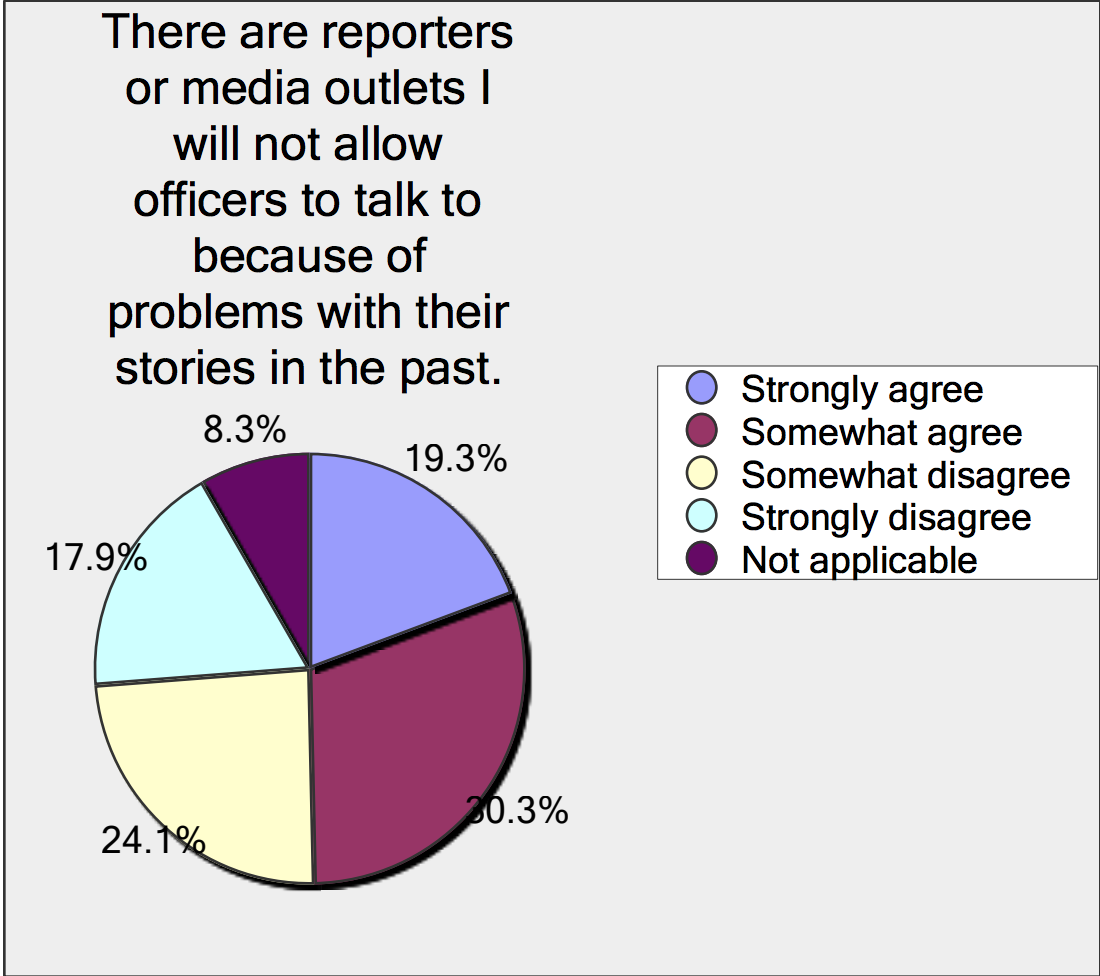

"The single most frightening statistic in the body of my research," Carlson said, "is that more than half of the PIOs we heard from admitted that they are determining who can cover them. They are banning entire publications and networks and shows. It would be different if it was not a government agency."

And the survey of PIOs found that "three-fourths feel it is necessary to supervise or otherwise monitor the interviews with police officers that they do grant."

Kathryn Foxhall, a member of SPJ's Freedom of Information Committee, told Poynter, "I don't think there is any question about it. When you talk with people who are under the oversight of a PIO, you get a massively different story than when you are free to talk to a source without that supervision."

Foxhall said that in the last couple of decades, universities have churned out public relations majors while the number of journalists is shrinking.

"PIOs are powerful because journalists are so reliant on them."

She said journalists find they have less time to produce original information so they rely on PIOs to feed them material. That reliance means journalists are more reluctant to push back on PIOs out of fear that they will get cut off from what access and information they do get. Foxhall said, "They are also powerful because they have created this chokepoint — we have to go back to them. We cannot go to anybody else in the agency."

One New York Times reporter told the National Press Club in 2017 that in the last 10 years she has had nearly zero access to career staff at the EPA. SPJ published a bushel full of other examples of serious reporters who chased significant stories and were blocked by PIOs.

Scientific American published a story that describes another disturbing trend called "close-hold embargoes" in which a government PIO calls together journalists and offers to give them a briefing about an upcoming announcement but in return, the journalist would not be allowed "to ask any questions of sources not approved by the government until given the go-ahead."

The story quoted New York University journalism professor Ivan Oransky, who is the founder of the Embargo Watch blog, as saying “I think it's deeply wrong.” (Embargo Watch also has an honor roll of agencies that lift onerous embargo policies.)

A PIO's view

Don Aaron has been a friend of mine for more than 30 years.

He is a former reporter who for 27 years has headed the Public Affairs office of the Nashville, Tennessee, police department. He has served under four police chiefs. He insists that when journalists call his office, they talk to a human, not a recording. At night, reporters get an on-call field captain. I asked Don why journalists have to go through PIOs to get to officers.

"If a reporter has something they are trying to pursue, let us help by being the conduit back to the person who has the knowledge," he said. "In this department, I have 'go to' people. If someone wants to talk about heroin, there are people in this police department who know a lot about heroin and opioids. If someone wants to talk about a cold case homicide, I will hook that person up with a detective. I have ways to reach those people that the journalist does not have."

He said that there are times when an officer responding to a call wants nothing to do with the media.

"When that occurs, it is going to fall to my staff to tell the reporter what the investigation is showing."

Sometimes, he said, officers might not like to talk on camera or they don't know what to say. Sometimes police don't want to appear to their peers to be grandstanding or publicity hounds.

"I had a sergeant who responded to a high-rise in Nashville where a senior citizen was contemplating jumping and the sergeant did a hell of a job helping the person get down and get the help they needed," he said. "I had to ask that sergeant to sit down and talk to a journalist about what he had done."

PIOs bypass media

Carlson said journalists have reason to worry that public information offices increasingly are taking their message directly to the public.

Social media makes it easy for officials to bypass face-to-face conversations with journalists.

This morning, Sheriff Ennis W. Wright of Cumberland County, North Carolina, posted a Facebook video where he explained how an officer-involved shooting unfolded. The sheriff’s department told Poynter that it was a way to get the sheriff’s view of the shooting in front of the public without doing a half dozen separate interviews or a news conference. It was the sheriff's first-time posting an official statement straight to social media. The sheriff’s department said that journalists are free to use the statement posted on Facebook. Some did just that.

The National Information Officers Association met in Florida last week. The conference included one session that told PIOs if they can produce content that journalists will run unedited:

"It's your story and your agency should be at the center of it, driving the pace and the main message. Breaking your own news – whether the story is 'feel good' or 'not-so-good' – is an effective way to be both transparent with those you serve and minimize unsavory coverage from traditional media outlets. When you break your own news by producing and distributing content, reporters and editors will likely use it. Whether a simple soundbite shot on a phone at the scene, or a fully produced video using fancy production equipment, media outlets in most markets around the country will often use your content and run it unedited."

Carlson said she worries most that younger journalists will not know a time when they could get direct access to the sources they need without going through a third party.

"As a teacher I found that young people do not realize this is not necessarily the best way to do things," she said. "They should not rely solely on PIOs to get information. If the PIOs won’t give it to them they are done; they cannot do the story. They do not understand that they have to do it a different way."

In my years as a journalist, professional public information officers like Don Aaron and others have helped me cover complex stories from the CDC, NASA or the U.S. Army; along the way, they have taught me some keys to working with PIOs.

1. Be upfront about what you are working on. Don't lie. You don't have to tell them everything you know, but it is my experience that if you tell a PIO that you are looking at problems in their agency, they will work harder to provide you with evidence that you might not know about. The evidence may not change your story but at least you will know the agency's best defense. I know this notion will be controversial, but when I am writing something that I know the subject of my story won't like, I sometimes share key pieces of the story before I publish it to hear any arguments against what I have written. I make sure the subject knows I am not asking for permission to report the story, but I am open to them poking holes in my findings before I report it. It makes the story bulletproof when you do report the story.

2. Admit what you don't know. Send a signal to the PIO that you want to learn nuances and details about their agency. Send the signal that you want to get the story right and it is fine for them to offer you background information and advice. PIOs can be especially helpful if you are new to a beat or new to a community. They appreciate it when journalists take time to learn how their agency works and to understand sensitivities they might have.

3. Personal contact is better than e-mail. Some public information offices make it difficult to speak to a person and want you to fill out request forms. But don't settle for such impersonal transactions. Personal interactions build trust. Give the PIO ways to contact you after hours. Encourage him/her to drop you tips and leads.

4. Be realistic. PIOs complain that journalists need everything "in a hurry," when with more forethought and planning, the deadlines don't have to be so urgent. PIOs might know how to get in touch with the people you want to talk with but actually tracking down busy people takes time. And even then, the person you want to speak with may have other obligations. You are not always a priority.

5. Don't expect a PIO to know everything. It is not possible for a public information officer to know about every study, every crime, every investigation or to know every employee of a big agency. University PIOs may represent tens of thousands of employees.

6. The journalists' job is not to always make government officials look bad. While journalists are not the public relations arm of the government, we should not forget that there are lots of honest, honorable, dedicated, brilliant and accomplished government workers who do important work. Be as willing to investigate "right-doing" as you are to report "wrong-doing." PIOs are a lot more likely to be open to you doing critical stories if you also seek out the legitimately good stories about their agencies too.

Researchers have documented the rise in government PIOs is connected to the rise in "watch-dog" journalism in the 1980s. Government agencies were trying to overcome the skepticism about government in the post-Watergate era. The same research showed that historically, journalists view public relations work more negatively than PR professionals view journalists. So one big reason for animosity between PIOs and journalists is a lack of mutual respect.

7. It's OK to push. In fact, sometimes it's your job. Don't settle for an easy-to-get PIO interview if there is another source that you know can illuminate the story better. Keep asking for access. If you are stonewalled, then it may be important for the public to know you did not get access to the person who has first-hand information for the story. Ask for alternatives. If an on-camera interview won't work, can you talk to the source by phone? Would it help if you invited the PIO to sit in on the interview? Is there a better place or time? Keep pushing. You are trying to get the best version of the facts that you can and it sends a signal that you are a pro and you are not just looking for the quick-and-dirty version of the story.

8. Follow up. When a PIO has helped a journalist with a story, journalists should show the courtesy of sending a link to the story when it is published. If the story is critical of the PIO's agency, it is a pro move for any journalist to call the PIO and be open to challenges and to correct any mistakes. If a PIO has been especially helpful, drop a note to his or her boss. Everyone needs an encouraging word now and then.

9. Does your media company model the behavior you want from others? Journalists expect answers when they call on governmental agencies, officials or businesses. But media companies are notoriously unresponsive when they find themselves in the news. You can expect to be filtered straight to corporate communications where a PIO-like person will manage your inquiry. It is exactly what SPJ and the other media groups are complaining about when it comes to how the government controls information and access. Be the change you seek.

Read the six years of SPJ-sponsored surveys:

– 2016 Survey of Police Reporters [PDF]

– 2016 Survey of Police PIOs [PDF]

– 2015 Survey of Science Writers [PDF]

– 2014 Survey of Education Writers [PDF]

– 2014 Survey of Political and General Assignment Reporters Across the Country [PDF]

– 2013 Survey of Public Information Officers [PDF]

– 2012 Survey of Reporters Covering Federal Entities [PDF]