Nancy Fishman, Project Director at the Vera Institute of Justice, confronts the journalists who attend Poynter's "Covering Jails" seminars with a simple question. "What are jails for?"

The typical responses she hears include words like "public safety." Then she says, "It turns out a lot of people in your jail are charged with non-violent misdemeanors. The people in jail are not who you think."

Fishman is one of the experts who I have partnered with to conduct workshops in four cities this year (New York City, Salt Lake City, Columbus, Ohio, and Oklahoma City). Our goal is simple; to help journalists cover the part of the justice system that holds more inmates than prisons and is locally funded.

Vera research says people awaiting trial sometimes are held in jail for months or longer because they cannot afford bail.

"We have seen people stay longer in jail awaiting trial than they would serve if they were convicted of what they are accused of," Fishman said. While sitting in jail, Vera research says, "employment, family relationships, finances, and community health are all disrupted, and this often has a disproportionate impact on those at the bottom of the economic ladder."

Journalists should pay more attention to jails

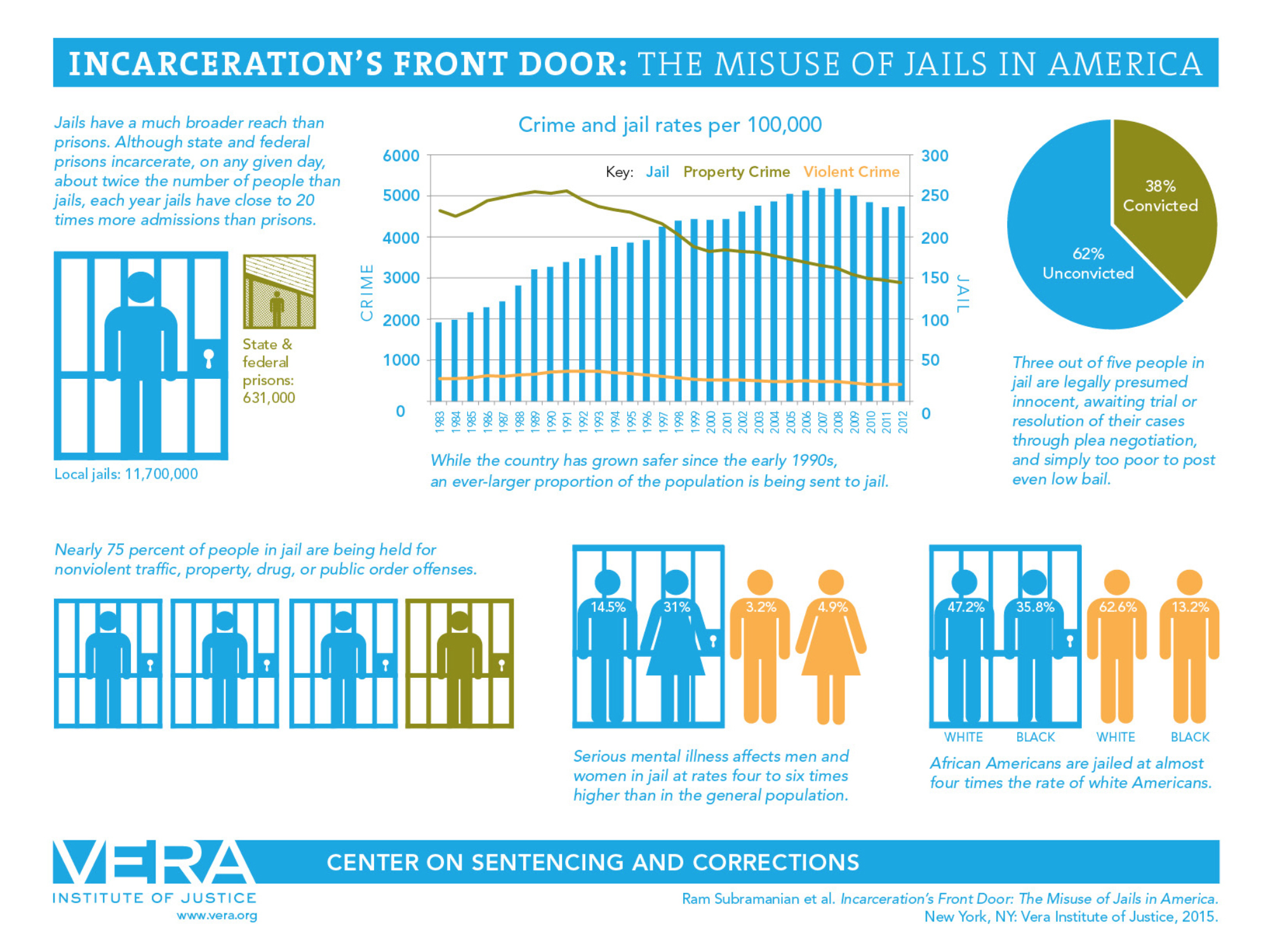

In our workshops, we have urged journalists to focus more attention on local jails because jails admit 20 times more people annually than prisons. Vera Institute of Justice says:

"The long-term trend is shocking: In 1982, for every 100 arrests, 51 people were booked into jail. By 2012, even after crime rates plummeted, that ratio had swelled to 95 out of 100, reflecting a knee-jerk use of jail out of step with threats to public safety. Today, jails log a staggering 11 million admissions a year—mostly poor people arrested for minor offenses who can’t post bail, and for whom even a few days behind bars exact a high toll."

The Department of Justice says 60 percent of jail inmates reported having had symptoms of a mental health disorder in the prior twelve months. Vera researchers found:

"People with serious mental illnesses are often poor, homeless, and likely to have co-occurring substance use disorders and, thus when untreated, are far more prone to the kinds of public order offenses and minor crimes that have been the focus of law enforcement in recent years and have helped swell jail populations."

About eight out of 10 people in jail who were diagnosed with a mental illness got no treatment while behind bars, and worse yet, jails are often noisy, brightly lit and constantly chaotic, all which can be especially disturbing to people with mental illness. Jails often resort to placing mentally ill patients in solitary confinement, sometimes as punishment for violating rules and sometimes to keep them safe from others.

African Americans are 3.6 times more likely to be in jail than whites. The incarceration rates in rural America is higher than in urban areas. The number of women in jails has skyrocketed. Vera's statistical expert, Oliver Hinds, told our workshop participants that in 1970, there were 8,000 women in U.S. jails. By 2014 the number exploded to 110,000 women in jail.

Two-thirds of people in jail have not been convicted and most people in jail are there accused of non-violent crimes.

Fines and fees

Poynter's "Covering Jails" workshops also focused on how local governments are adding fees to fines in order to pay for jail costs. These fees can add up fast, especially when they are coupled with interest rates that rival the priciest credit card rates.

It is not a new idea. One Michigan county started charging jail prisoners for medical care back in 1846. The Brennan Center says that same county, 100 years later, was charging prisoners for "room and board, work release, physicals, dental visits, medication, prescriptions, nurse sick calls, and hospital medical treatment."

Jails now often add fees to everything from laundry costs to toilet paper and clothing.

"If you don't have enough money you don't know which one to pay first," Fishman said. "It is like, 'do I pay the electrical bill, the water bill, the school fee?' A lot of them you will not pay if you are not convicted. But some fees you will pay even if you are not convicted."

The Atlantic reported that when prisoners fail to pay the fees, they may wind up back in jail, running up more fees.

"What’s more, in 44 states, former inmates can be re-incarcerated if they “willfully” fail to pay their fees. But the determination of whether an individual is “willfully” trying to make payments is very much up to judges; some judges decide that a former prisoner’s inability to get a job can constitute a lack of willful attempts to pay fees — resulting in him ending up back in jail and facing even more fines.

In Charlottesville, Virginia, the courts allow prisoners to "work-off" their fees and stay out of jail. Stateline, a Pew publication, said "Georgia, New Mexico and Washington state, for example, let people work off debt with credits commensurate with the minimum-wage. Michigan in some cases allows people to reduce their debt by meeting education requirements like getting a GED diploma."

Vera expert Elizabeth Swavola said Washington State recently passed legislation that keeps jails from charging interest on jail fees while the prisoner is serving time. Look at this story from 2014 and you will understand how high-interest fees on jail fees can mount up.

Journalists can turn to the Fines and Fees Justice Center for news about local and state incarceration fees. The National Center for State Courts also has a 2017 deep study on fines and bond trends in state courts. Journalists will find co-authors of the study from many states.

Bail reform

Across the country, states are changing laws requiring bail for release from jail.

The New York Times recently reported that "as bail has grown into a $2 billion industry, bond agents have become the payday lenders of the criminal justice world, offering quick relief to desperate customers at high prices." The result, the Times said, is that jails keep the poorest, not the most dangerous defendants in jail.

WYNC has extensively covered jail reform efforts in New York.

Another partner in the Poynter Covering Jails workshops, The Marshall Project, collects daily stories from around America on problems with the bail system. Even when lawmakers do not change the bail system, charitable groups in Boston, Brooklyn, Nashville, and Seattle formed to raise money to provide bail for people who are too poor to pay to get out of jail.

How to get the public to care about jails

Jails are a hot topic. On July 1, CNN will air a special documentary called "American Jail" by Academy Award-winning director Roger Ross Williams. The film asks the basic question of whether jails are doing anything positive for society. The film also includes our seminar expert Nancy Fishman. (See the trailer here.)

Still, it can be difficult for journalists to persuade bosses, much less the public, to care about what is happening in jails. The raw cost of operating jails could be one way to attract attention. Jails are expensive. "The annual cost, per incarcerated individual, averaged $47,057 in the 35 jurisdictions that responded," Vera's survey shows.

Vera conducted a public survey and found 62% of Americans agree that building more prisons and jails is not an effective way to improve communities. They want the money spent, instead, on things like schools.

The only sure way to cut costs is to cut the number of people in jail. Big cities like New York, Philadelphia and Oklahoma City have declining jail populations, while smaller communities are still filling more jail beds. Vera compiled an interactive map to help journalists see county-by-county incarceration rates. Note that pretrial incarceration rates in rural county jails increased 436 percent between 1970 and 2013. (Learn how to use the data tool with this tutorial video.)

The New York Times mapped the government contracts with private shelters across the country (see map) to house children separated from parents at the border while the adults arrested by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement may live locked up in county jails from coast to coast. In many cases, particularly in the South and West, local governments are building bigger jails to house state and federal prisoners, so the jails are becoming revenue sources. Vera said the feds typically pay more per day for local jails to hold prisoners compared to state reimbursements.

Vera found that local governments, faced with overloaded jails, build bigger jails.

"When they do that, they find ways to fill those new jails," Fishman said. But communities that do not expand jails are finding ways to avoid sending prisoners there.

Vera discovered that "jail expansion in rural counties is oftentimes not a slow, inevitable trend, but a result of a new facility opening. In Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, for example, a jail facility built in 1993 was intended to alleviate overcrowding. The new facility increased the jail capacity from 150 beds to up to 650—far more than the parish needed at the time. But soon enough, by 2008, the jail was full—and as the data show, the pretrial jail population (those legally presumed innocent while they await the resolution of their case) spiked and exceeded the statewide average. Earlier this year, the parish opened a women’s facility to make more room in the main jail."

The Marshall Project, pointing to Vera's trend data, concluded:

Even though the jails in the largest counties get most public attention — think of Rikers Island in New York City, the Los Angeles County Jail in Los Angeles, the Cook County Jail in Chicago — these jails have not grown the most, nor do they have the highest incarceration rates. On the contrary: jail incarceration rates have been growing faster in mid- to small-size counties. Looking at counties with more than 250,000 county residents, those with the highest jail incarceration rates today are:

- Clayton County, GA (962 per 100,000)

- Shelby County, TN (876 per 100,000)

- New Orleans, LA (861 per 100,000)

And the longer a prisoner spends in local jails, the more likely they are to re-offend, as a study by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation found.

"Even a relatively short period in jail pretrial — as few as two days — correlates with negative outcomes for defendants and for public safety when compared to those defendants released within 24 hours. While results varied by length of detention and risk level, in virtually every category, those detained were more likely to be rearrested before trial, to receive a sentence of imprisonment, to be given a longer term of imprisonment, and to recidivate after sentence completion."

Streamline case processing

Vera researcher Elizabeth Swavola told Poynter workshop participants that one way to move people out of jails is to keep cases moving through the court system. Clogged dockets delay hearings, frustrate defendants and even encourage court no-shows if time after time the defendant misses work to appear in court only to have a case delayed.

Some court systems have called in retired judges to clear backlogged dockets.

Nancy Fishman said one of the most successful ways to ensure that defendants show up for court is to send them a reminder.

"It's like what your dentist does to remind you to keep your appointment," she said. "It turns out people usually do what they are told to do if they are reminded."

Fishman also said, surprisingly, there is no evidence that higher bail increases the likelihood that a defendant will show up for court.

Opioids and jail

Another Poynter workshop teacher, Dr. Lipi Roy, the former Chief of Addiction Medicine for New York City jails, including Rikers Island, said "the largest substance use and mental health facilities are jails and prisons in the U.S." Dr. Lipi said by some estimates, a fourth of inmates are addicted to opioids.

The medical journal JAMA Psychiatry found that opioid overdose deaths dropped by nearly two-thirds among recently incarcerated people in the first year of a Rhode Island's new program that screens and provides addiction medicines to all state inmates.

"Rhode Island … provides all three FDA-approved addiction medications, methadone, buprenorphine and a long-acting, injectable form of naltrexone known as Vivitrol, to all inmates. According to the study by Brown University researchers, the program not only reduces overdose deaths after the inmates are released, but also increases the likelihood they will stay in treatment and avoid getting arrested again," Stateline reports.

Dr. Roy said it is critical that jails provide treatment for addictions. And some are trying. USA Today this week reported on a handful of experiments, in Hamilton County, Ohio, where the jail is launching a "buprenorphine-aided withdrawal program."

USA Today pointed to other jails that have launched addiction programs:

- Snohomish County Jail in Everett, Washington, started a pilot program in January using suboxone, KING-TV, Seattle reported.

- Jefferson County Jail in Golden, Colorado, began in April to use naltrexone, a drug that works in the brain to keep opiates from working and helps stop cravings, for its addicted inmates, KUSA-TV, Denver reported.

Dr. Roy said jails routinely provide medical care for all sorts of illnesses, and said addiction "is a chronic medical illness, a disease of the brain, where relapse is expected." But, until now, jails have not treated addiction as an illness, but as a moral failure.

"Most people with addiction, once connected to the appropriate treatment and recovery services, get better," she said.

Get local

Poynter's "Covering Jails" workshops are funded by a grant from the MacArthur Foundation's Safety and Justice program.

The same funder is helping 20 communities around the country innovate jail reform. Philadelphia, for example, is one of those communities that got $3.5 million in MacArthur funds to renovate its jail system.

As a result, MacArthur said, "the Philadelphia Department of Prisons announced plans to close the House of Correction, the oldest operating jail in the City of Philadelphia, citing a 32 percent decrease of the city’s incarcerated population since July 2015."