Within minutes of the school shooting at Parkland High School in Broward County, Florida, video of the shooting, including shots and screams flowed online. Graphic video of a bloody body gave a hint of the horrors that would unfold. Another student snapped photos while crouched in a classroom while another recorded SWAT officers herding children out of an auditorium. I am not linking to those images here. You can find them easily if you want to.

We have been here before. So many times. And have to have the conversation again about:

- How much to show

- How often to show it?

- If we don't show it on TV are the guidelines different for online?

Maybe, we could argue, that we should not shield the public from the violence. If the public, if elected officials saw the images as they really are, maybe we would have a more serious conversation about gun violence.

Or maybe, we should argue that showing the graphic images rewards the shooter and encourages others. It is predictable as the sunrise that this shooting will be followed by a wave of threats that schools around the country will endure in the next week. It happens after every widely covered mass shooting, experts say.

What is the reason for showing graphic images?

It is totally justifiable to show graphic images if the truth is in doubt. If, for example, there was any doubt that there had been a shooting, then the images would show a version of the truth that did not otherwise exist. We can point to videos of police shootings, for example, as ethically justifiable graphic video that was vital evidence about what happened and who was culpable.

If you have access to graphic video and don't show it: Explain why you are not showing it. That helps educate the public about your decision-making process.

How will the fact that these images involve young people, most likely minors, affect your decision-making differently than showing images of adults as we saw in the Las Vegas shooting or the Pulse nightclub shooting? Journalists should be especially cautious about communicating with students on social media or interviewing the young person unless the kid's guardian is a part of the decision to participate. If a parent does give approval, explain that to the public.

If you do show graphic images

Explain why you believe the images are vital to the public understanding. This is more than the "Warning some of these images may be disturbing" message that TV and online journalists often offer as a "disclaimer."

Tone and degree of coverage

If it is justifiable during the initial breaking news to show graphic disturbing images and video, the justification becomes less over time, as the details of the shooting becomes clearer. Just because you used the video once is not the reason to keep using it.

Cable TV news looped the video of children running from the school over and over for hours. Repeated airing of those images will eventually have the effect of exaggerating the danger that students face in schools when, experts say, statistically school is the single safest place for kids each day. That fact is increasingly hard to swallow after 18 school shootings already in 2018.

- Homicide is the second leading cause of death among youth aged 5-18. Data from this study indicate that between 1% and 2% of these deaths happen on school grounds or on the way to or from school. These findings underscore the importance of preventing violence at school as well as in communities.

Most school-associated violent deaths occur during transition times — immediately before and after the school day and during lunch.

Violent deaths are more likely to occur at the start of each semester.

Nearly 50 percent of homicide perpetrators gave some type of warning signal, such as making a threat or leaving a note, prior to the event.

Firearms used in school-associated homicides and suicides came primarily from the perpetrator’s home or from friends or relatives.

Does naming the accused shooter encourage or reward violence?

Without a doubt one of the debates that will begin by the time you read this is whether journalists should name the accused shooter. The New York Times included a photo of him holding a pistol in a social media post. (The pistol in the photo has a red tip, which probably means it is not a real pistol but possibly an air-soft pistol.) Well-meaning journalists will no doubt argue that naming a suspect rewards that person with some sort of celebrity status. My own view, which I have is that "who" is accused is an important part of the story. I have explained in previous columns that news coverage of high profile crimes does contribute to a killer's celebrity and celebrities generate followers. In a previous column I explained:

Investigators found that the shooter who killed children at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., kept detailed records of mass shootings. He was preoccupied with the killings at Columbine High School in Colorado. He is not the first. Around the globe, killers and attempted killers said they wanted to commit a Columbine-like attack. Other high-profile cases involve Columbine killer devotees who took their own lives in sympathy with the Columbine shooters. And The Washington Post once noted, "Marilyn Monroe’s suicide in 1962 allegedly triggered a spike in suicide among young women. Shootings by disgruntled workers at U.S. Postal Service facilities during the 1980s became so relatively common that the phrase “going postal” entered the language. The snipers who terrorized the Washington area in 2002 may have touched off imitators in Ohio, Florida, Britain and Spain shortly thereafter.

After the 9/11 attacks, it was clear the nation needed to know the names of the attackers and their supporters. We needed to find out how they slipped through airport security security and how to fix it. As The Washington Post pointed out, the extensive reporting the man who carried out the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting "helped expose flaws in Virginia’s mental health system, leading to reforms." And the Post said extensive reporting on the Columbine shooting focused new attention on troubled teens.

As soon as the accused shooter's name was public Wednesday afternoon, social media exposed what appeared to be threatening social media pages that may have been posted by the accused. We have been through this debate many times before as well. I explain:

Whether a photo glamorizes or aggrandizes a killer may be in the eye of the beholder. One of the most debated cases of self-aggrandizing photos involved the Virginia Tech shooter who sent NBC News a video and photos of himself posing with weapons. Journalists struggled with whether to show the photos, how many to air and for how long. Even staged images like those of the Virginia Tech shooter may give us insight into the brazenness and rage of the killer.

Some criminals flat out crave publicity. Bonnie and Clyde grabbed headlines and built their legend by mugging with guns. Just as damaging as photos may be, the monikers that journalists apply to suspected killers such as "mysterious," "ruthless," or "dark" are as well.

Describing the weapon

Police say the shooter in this case used an AR-15. You will hear it routinely described as an "assault weapon" and just know that is a controversial description. Pro-gun folks now use a different term for these weapons. They call them "sporting rifles" which is a reference to how the popular AR-15 is often used in shooting competitions. It is highly accurate at long distances and has very little recoil. The New York Times profiled the weapon in this video.

The AR-15 is a semi-automatic rifle, legal in Florida. It does not require registration. A semi-automatic weapon requires a shooter to pull the trigger for each round. It is not a machine gun, which is a fully automatic highly regulated weapon.

The NRA summarizes Florida gun laws that are among the least restrictive in the country:

You will also hear police report he had "multiple magazines" of ammo. A magazine is the device that holds the rounds of ammo and fit into the rifle. Magazines can hold 10, 20, 30 or more rounds.The rounds are fed by a spring and a new round loads every time a shot is fired until the ammo is emptied. Some places, like California have recently passed legislation that limit the number of rounds that a magazine can hold. Florida has no such regulations.

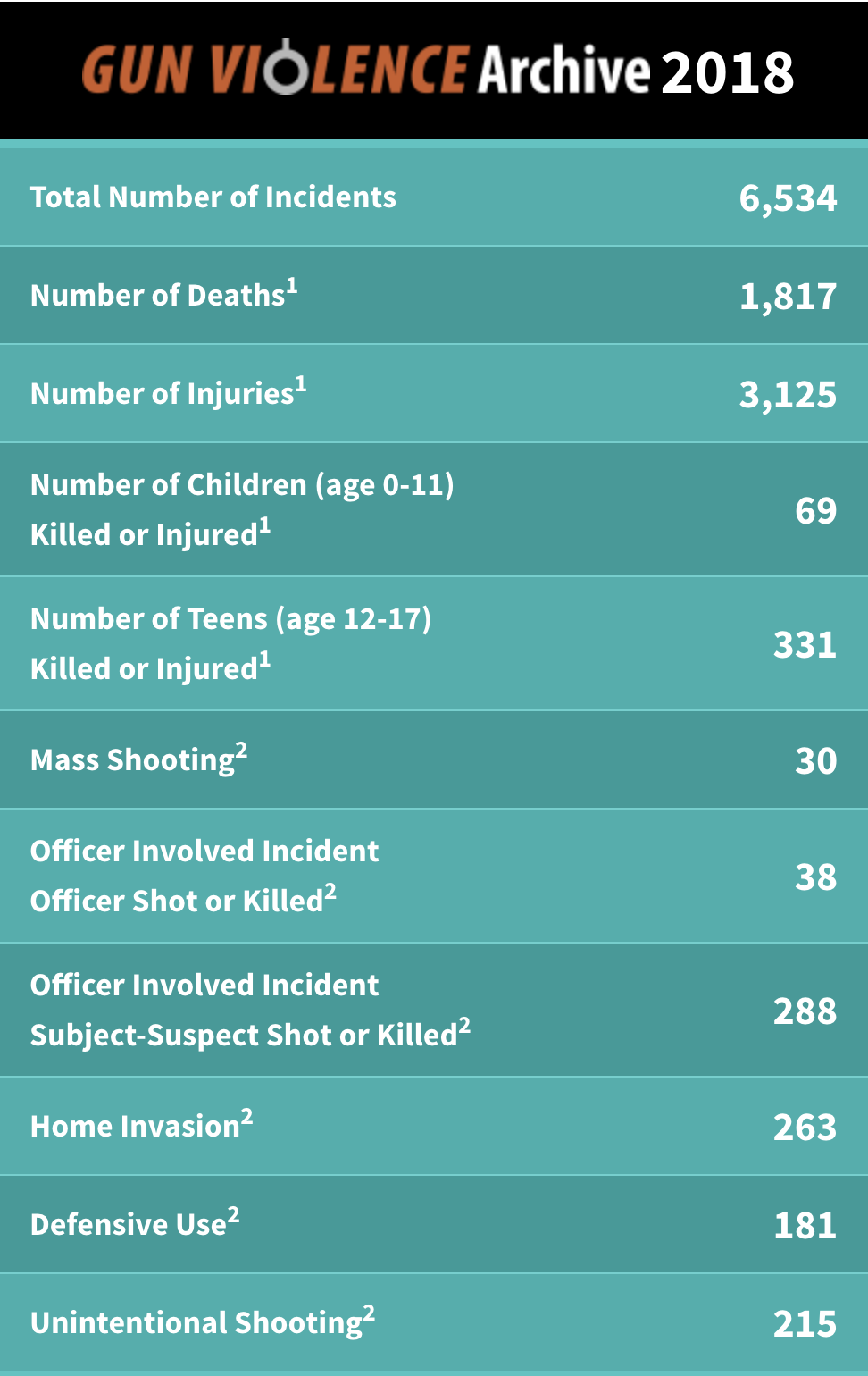

This data from http://www.gunviolencearchive.org/ is the product of the website collecting /validating reports from from 2,500 sources each day. Because the data is based partly on news reports, the data may not be exact and could even be an under-estimate. About annual suicides not included on Daily Summary Ledger.