If you’re curious where all the fake news on your News Feed comes from, there’s a new resource that could help you become an internet sleuth of your own.

Today the Public Data Lab, a network of researchers, journalists and organizations, released a field guide for detecting and investigating online misinformation. The free and open-access guide, aimed at helping students, journalists and educators, contains a number of “recipes” for tracing things like trolling practices, the circulation of viral memes and the financial incentives that hold it all together.

It’s like a cookbook, but for fake news.

“The value of the guide is that it provides practical, simple, step-by-step instructions for journalists to actually dive into these networks and help find and visualize connections and patterns,” said Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft — a project of Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy that supported the guide — in an email to Poynter.

“Too much of the reporting on this subject is not based on the data, and while not everyone is a computational journalist, the recipes outlined in this guide mean that most people can run some basic analysis of the online disinformation networks they are writing about.”

The guide comes as a result of growing demand for understanding how misinformation, platforms and politics come together online, according to a Monday press release, and its primary audience is students, journalists and researchers who want to investigate fake news on their own. Several universities and media organizations have tested it since a sample was released in April, notably BuzzFeed News in an investigation of ad trackers on fake news sites.

Still, the Public Data Lab’s guide, which is part of a larger research initiative on misinformation, isn’t exactly new. There have been several other debunking how-tos and tool lists published in the past couple of years — including from here at Poynter. But what the field guide lacks in fundamental originality it makes up for in comprehensiveness.

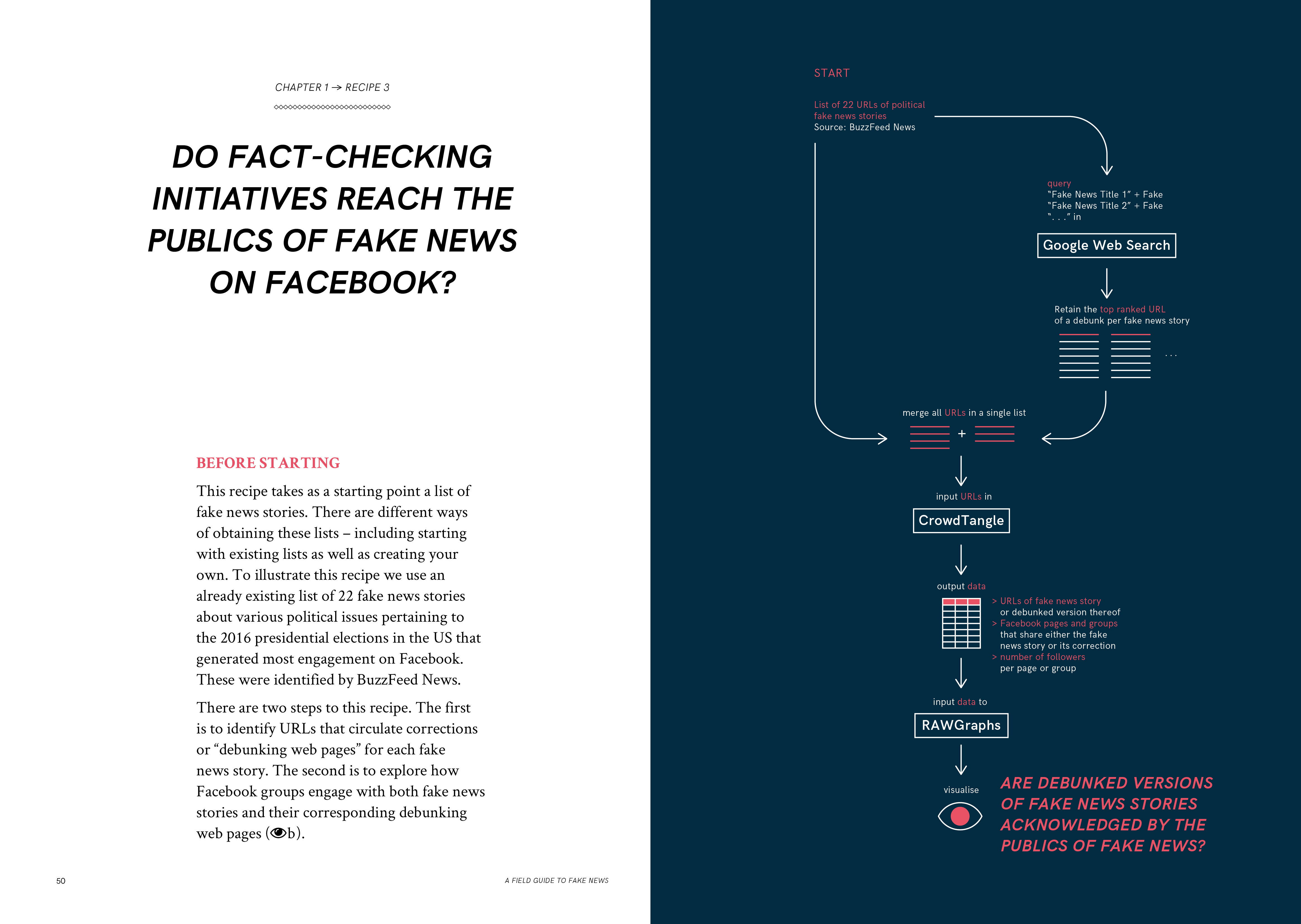

The more than 200-page report, which is based on contributions from researchers based at several universities around the world, comes complete with several detailed how-to graphics for investigating the causes and networks of misinformation online. Its five chapters range from “Mapping Fake News Hotspots on Facebook” to “Mapping Troll-like Practices on Twitter” and go much more in depth than other existing guides on sighting misinformation.

To Wardle, that’s the project’s key distinguishing attribute.

“In terms of tools, there are very good resources for teaching people how to 'spot' misinformation, as well as image verification tools and processes, but there is actually very little in terms of helping journalists understand the networks that exist,” she said. “These recipes are great for teaching journalism students basic computational processes, as well as more established journalists who want data to support their reporting.”

The entire report is under a Creative Commons Attribution license and available for download here. There’s also a Github page so that it can be translated into other languages.