A simple prompt opens a world of possibilities on this campus that once catered to commuters and where community can still be hard to find.

As we reach Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, the air turns cooler as fall finally reaches us on our sixth university visit on our Poynter College Media Project journey. Fresh from the college-town vibe of Ann Arbor, we cross the mighty Mississippi on our drive from the St. Louis airport to Edwardsville, where wide open stretches of farmland line the interstate. I admire the crepuscular rays — Fara Warner taught me that word, crepuscular, to describe what I had always called “hand of god” streams of cloud-bursting light. Crepuscular skies, I nod, feeling at once at home in the Midwestern-ness of our new surroundings.

Winding drives lead into the mostly brick 1970s-era campus of Edwardsville; glimpses of trailheads hint at the forested discoveries just beyond our view. The landscaping is colorful, lush and carefully maintained. Tidy rolls of hay decorate one roadside field. Families of deer boldly lope across streets and between trees just a few hundred feet from classrooms. The farm scene belies southern Illinois’ industrial side. Just a short drive away, a massive gasoline refinery belches smoke into the air. Workers on a new oil pipeline tumble into hotels just off the interstate every morning, less-than-fresh after their long night’s work.

Many students on this campus hail from St. Louis and its suburbs. Most, though, come from other cities in Illinois, including Chicago. Edwardsville, which began as a satellite to the research-focused Southern Illinois University Carbondale, now has a higher student population and continues to grow while its rural predecessor’s enrollments continue to slip.

As their school grows — and Cougars outnumber Salukis — students on the Edwardsville campus bear witness to the growing pains. More than half of new first-year students live on campus. And as on-campus housing options grow, so does friction between students from different backgrounds pursuing different roads to degrees.

Commuters versus dorm-dwellers. Big city natives versus farm-living locals. Today’s SIUe, we learn, occupies more than a geographical crossroads. Even the name of the independent student newspaper, The Alestle, incorporates three distinct identities that have defined the school’s past. The word “Alestle” is an acronym that combines the three cities where the school has been located: Alton, East St. Louis and Edwardsville.

The Alestle’s program director, Tammy Merrett, wrote SIUe’s Poynter CMP application. It was the only non-student submitted application we selected, and noted core challenges facing its student journalists:

“We have had racially motivated speech incidents and protests over the last four years. We have also had free speech issues and litigation. This can be a tense place where we need better understanding of each other, but it’s not clear that the administration knows how to go about that.”

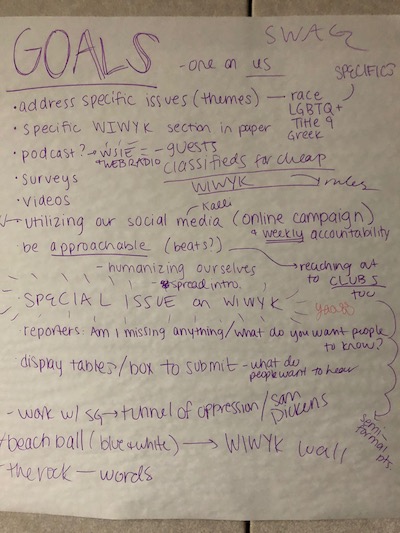

Merrett, who works closely with the small, tight-knit staff of student journalists, also highlighted an existing project the staff had been planning. Its name caught our attention right away: “What I Wish You Knew.” Merrett, a college media veteran who cares deeply for the students she serves, described it as an opportunity for the community to learn more about its disparate members — administrators, faculty, staff and students.

The “What I Wish You Knew” concept intrigues us, even before we get to know more about the 14 earnest and dedicated Alestle newsroom staff members. We envision narrative approaches that cross media and explore the realities and misconceptions about groups that have clashed in the past.

While the SIUe student population is nearly 75 percent white, as we step into the main student center, it’s clear that both black and white students dominate this space. The Alestle offices sit on the second floor of the center, upstairs from the Starbucks and near the office of diversity and inclusion. All around, cushioned booths and soft chairs offer plentiful spaces for napping and reading, for sharing meals with friends or meeting for class projects.

All of the Alestle staff members attend both days of training — Merrett helps ensure this by counting the sessions as part of their paid work time. As they arrange their chairs in an open “U” shape, they laugh and share inside jokes with the easy familiarity that shared deadlines can bring. They are a diverse bunch: some first-years and some seniors, some with a passion for visuals and design and others obsessed with news, some who stumbled into journalism and some drawn to the staff because of their love for writing and sharing stories. One shares her story of how losing her family home in a tornado exposed her to the importance of telling true stories and capturing hard realities. Another talks about Spike Lee and Karl Marx, both of whom added valuable perspectives not only to her world view, but also to her understanding of the importance of story.

While the group grows animated as they talk about hate crimes on campus and struggles with getting campus police cooperation, they don’t seem too excited about “What I Wish You Knew.” Our visit, we learn, comes not long after the inaugural “What I Wish You Knew” event, a panel discussion that focused more on procedures than personal experiences. While some of the staff thought the content was valuable, only handful of people attended, including some editorial staffers.

While we had imagined a “What I Wish You Knew” that transcended a public event and maximized The Alestle’s print and digital presence, they had been thinking small — and feeling less than hopeful as a result.

What if, we ask, they used the powerful prompt as a tool to enrich their journalism on a regular basis? What if they view it as a way to launch new content and explore new forms of storytelling as they raise their profile on campus and build bridges across divides?

As they break into small groups, they brainstorm ways to engage their fragmented campus, using “What I Wish You Knew” as a guide. One group suggests starting the project by featuring staff members’ answers to the prompt. The staff is off and running, planning new stories and listing groups ripe for collaboration on events and expanded coverage: the small but influential Greek groups on campus, the Honors program, sports teams and alumni.

It seems fitting to honor their work by sharing part of my own “What I Wish You Knew” list here:

“What I Wish You Knew” is that SIUe is a place with big hearts and dreams. A place where students work to find their voices and share them. A place where stories about the challenges of trans-housing and unsolved hate crimes and property destruction tell as much of the story of America as do the breathtaking skies setting over acres of farms and the smelly, smoke-spewing refinery.

“What I Wish You Knew” is that the Edwardsville Cougars want to do more and be more than their predecessors. They want to create an open dialogue with their peers and offer pathways to community both in their publications and on their campus, from throwing a kick-off bonfire with apple cider (this suggestion took the excitement level up multiple notches) to gathering stories from classmates as they pass through campus.

“What I Wish You Knew” is their pride in their Honors program; their hopes for finding jobs that fulfill them; their plans to offer media platforms for marginalized groups on campus.

“What I Wish You Knew” is how they laugh as they awkwardly “floss” in their small group, how they talk thoughtfully about their inspiration and how they understand the power of story to make a difference in the world.

“What I Wish You Knew” is how their faces light up when, at the end of our time together, they start their work by asking peers from a median class that joins us: “What do you wish I knew about your life at SIUe?” How, after an awkward moment of sitting across from strangers, they lean toward one another and listen deeply. How they share what they hear about feelings of isolation, the lack of a supportive community and the pain of racism. How the students they interview reflect on their experience, sharing how it felt to answer the prompt. How they take a moment, then say they feel heard. How they admit that they had never before articulated how much their isolation at SIUe hurts. Or why. And how it feels good to connect through story.

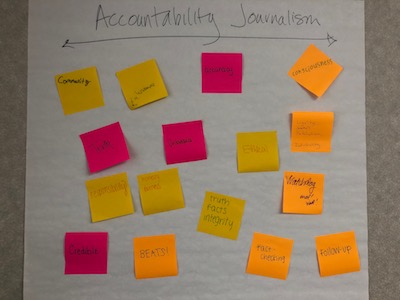

As we leave Edwardsville, we know that The Alestle staff will host another event, but they are now also determined to allow their readers in. They will try new forms of media to reach new audience members and engage them as collaborators in story. As they continue to push the administration and campus police to share public records more willingly and in a more timely fashion, they will offer opportunities for people with different opinions to share their views. They will move beyond seeing fairness as a “he said, she said” proposition and more as a way to show context and truth and not false equivalencies.

The beauty of SIUe, in many ways, is the student media members’ passion to learn what others wish they knew, share it and put it into action. They will start with a special issue that explains what they wish their audience knew about them as a staff and as an operation. Dispelling myths and stereotypes, they will embrace transparency for themselves first, before asking it of others. They will lead by example and in so doing, create new pathways on a campus in flux, where growth without community can easily lead to more conflict and, ultimately, lost opportunities for students, faculty and administrators alike.

Go Cougars.

The College Media Project is funded by a grant from the Charles Koch Foundation.