Editor's note: This article has been updated with additional information from Chequeado.

DURHAM, North Carolina — Bill Adair opened the meeting by projecting a stock photo of a robot.

Then another.

And another.

Admittedly, selecting a different bot photo for every story about automation is a pretty trivial problem for journalists covering technology (including me). But it is anecdotal evidence of the rapid growth in automated fact-checking over the past year.

Last week, 48 people from four countries gathered at Duke University to discuss the future of automated fact-checking. Leading the pack was Adair, co-director of the Duke Reporters’ Lab, which launched the Tech & Check Cooperative with $1.3 million in funding in September. The initiative brings together researchers and practitioners to share best practices for automated fact-checking and funds the creation of new tools.

During the two-day meeting, fact-checkers demoed their platforms, pressed representatives from Facebook and Google for more information on how they’re approaching misinformation and discussed the impetus for developing common sets of standards. And, looking back at the progress that was made over the past year, there was plenty to talk about.

“The conference showed that automated fact-checking is growing much faster than we expected,” Adair, the Knight Professor of Journalism & Public Policy at Duke, told Poynter in an email. “We’re able to build and test things today that seemed like a distant dream just a few years ago.” (Disclosure: The Reporters’ Lab helps pay for the Global Fact-Checking Summit.)

In January, Chequeado, a fact-checking outlet based in Argentina, launched Chequeabot — a tool that automatically finds fact-checkable claims in news text and sends them to the newsroom. Two years ago the project was just a draft idea, Editorial Innovation Director Pablo Martín Fernández told Poynter in a message.

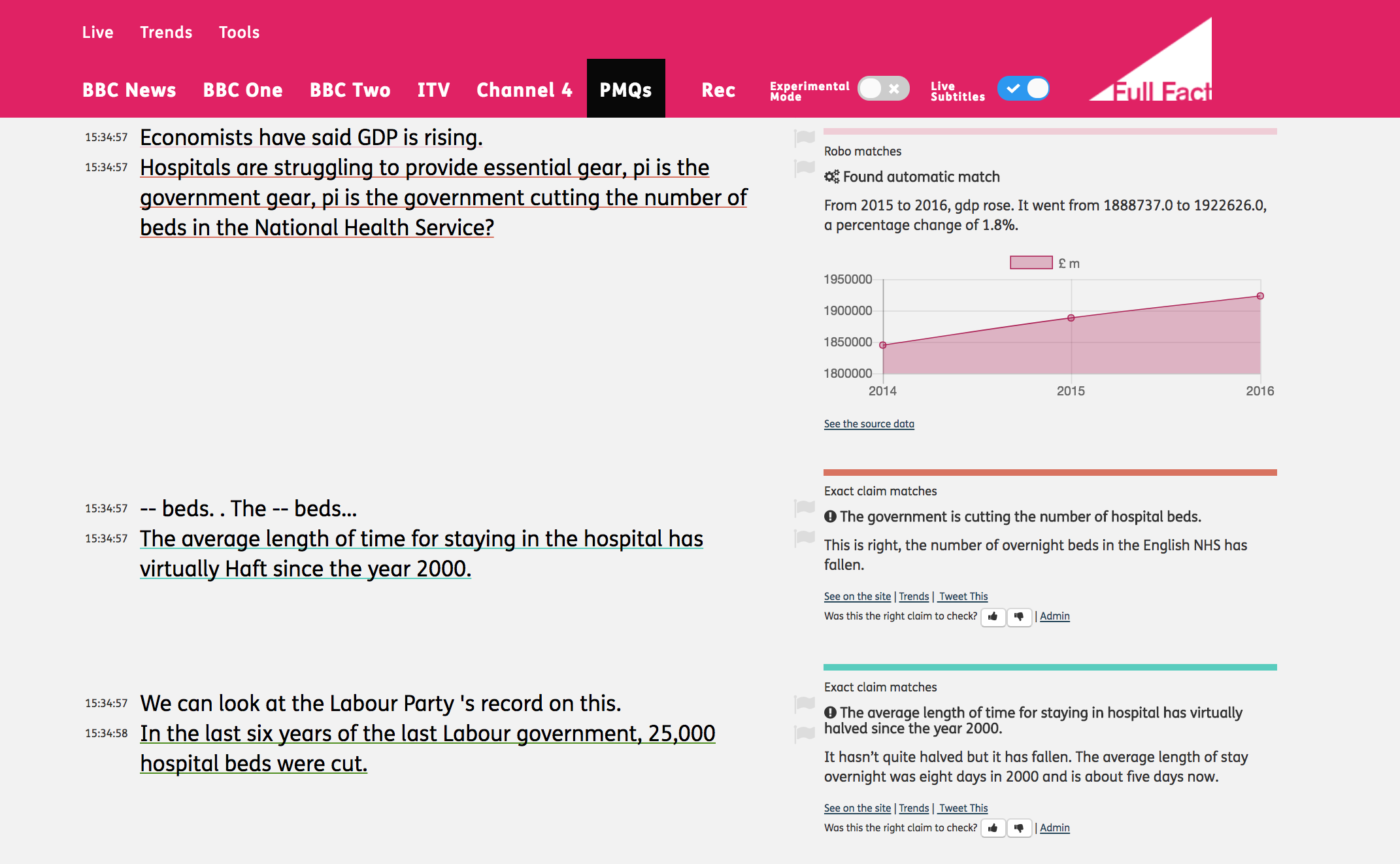

Other projects are similarly sophisticated. At Tech & Check, Mevan Babakar, a digital product manager at Full Fact in the United Kingdom, showed off the platform whose concept inspired Chequeabot: Live.

The tool, which automatically scrapes Parliament and BBC transcripts for claims, now creates bot-generated fact checks based on official statistics — in addition to matching claims with existing fact checks. That’s a far cry from the original Tech & Check meeting in 2016.

“Two years ago they weren't even prototypes,” Babakar told Poynter in a message.

Woah: @MeAndVan says @FullFact's Live tool now automatically matches claims with official government statistics, then generating "robo-checks" based on the data https://t.co/gbz7xcA4g9

— Daniel Funke (@dpfunke) March 29, 2018

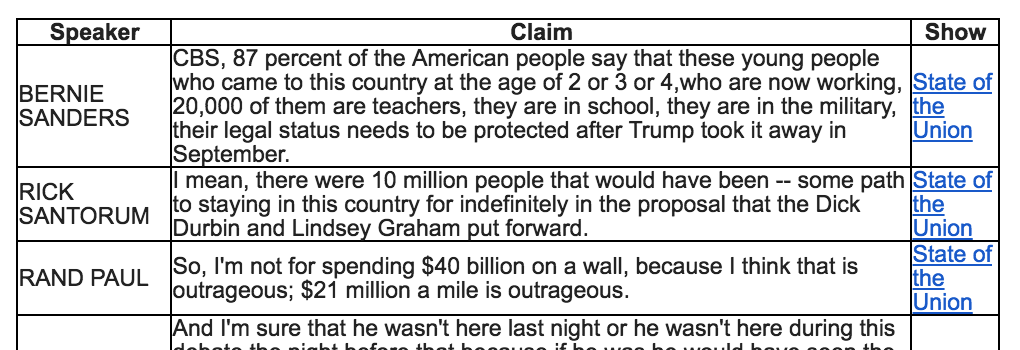

Finally, there’s the Reporters’ Lab’s own automated technology. In January, it deployed a feature that automatically scans CNN transcripts for fact-checkable claims using the API of a tool called ClaimBuster, which was created by computer scientists at the University of Texas at Arlington. Then, it sends them to fact-checking partners like PolitiFact and The Washington Post Fact Checker for potential coverage.

Still, despite the progress, the current state of automated fact-checking is limited. Among the challenges highlighted during the Tech & Check meeting:

- Parsing through messy TV and government transcripts to find fact-checkable claims and identify speakers

- Working around natural-language processors’ English bias to develop tools in non-English speaking countries, as well as keeping them up-to-date with political language

- Getting and maintaining access to reliable official datasets

- Avoiding duplication of efforts as fact-checking tools get developed around the world

- Getting funding from major donors in regions where it’s less easily available

That’s a lot of obstacles. But Adair said they’re solvable.

“I think our biggest challenge is getting a large enough database of fact-checks so our apps and tools will get a sufficient number of matches,” he said. “The meeting showed the value of bringing together all the players — the fact-checkers, developers and computer scientists.”

One of those fact-checkers, Aaron Sharockman, executive director of PolitiFact (a Poynter-owned project), came up with a “Christmas list” based on the limitations of automated fact-checking that were identified at the meeting. Here are his rough notes, which he sent to Poynter in a message:

- Process to make hyperlinking in articles super easy, replace copy and pasting.

- Making sourcing more efficient. Can we create a CRM of sources. Can we easily plug in material from sources into our article? Can we easily/automatically create citations of the sources we talk to?

- Clustering similar work. Build a tool that identifies similar fact checks or work that we can use to reinforce our credibility.

- Help us figure out what experts we can trust.

Karen Mahabir, editor of the Associated Press’ fact-checking project, said she’d like to see which claims are resonating the most with her audience. Linda Qiu, a fact-checking reporter at The New York Times, added that she’s concerned about the growing potential for AI-powered fake videos and that she’d like to see the Reporters’ Lab broaden the scope of claims that ClaimBuster sends to fact-checkers.

Those are some pie-in-the-sky ideas, but are they possible to achieve? Adair thinks so.

“I think most of Aaron’s (and Linda’s and Karen’s) wish list is achievable,” he said. “It’s just a question of whether enough fact-checkers will benefit from each one to justify the resources necessary to build them.”

And Babakar agreed.

“This stuff is all more dependent on people working together well, rather than anything technologically complex,” she told Poynter in a message regarding Sharockman’s first point.

But some of the other wants are more complex. Clustering, for instance, sounds nice in theory, but Babakar doubted that developing tools to address it would be worth the time.

“This is possible but how much overlap do fact-checking (organizations) actually have? We very rarely cover stories across international boundaries,” she said. “Clustering depends on what your definition of a good cluster is in the first place, and that might be a hard thing to agree across organisations and people.”

And then there’s finding trustworthy experts. Babakar said that it might be possible to develop tools to detect who’s been cited where, but “to actually figure out who is trustworthy is not possible.”

Regardless, some solutions to automation’s limitations are already being built. The Reporters’ Lab is building a tool similar to Full Fact’s Live platform that will identify some of the most-frequent factual claims, as well as broadening the Tech & Check Alerts it sends to fact-checking partners. The International Fact-Checking Network is developing a plugin that will help fact-checkers structure their source database and store them permanently.

And in the meantime, the Tech & Check Cooperative will keep bringing fact-checkers, researchers and the platforms together, Adair said. It’s not Christmas yet.