What started as a pilot project 16 months ago is now one of Facebook’s primary weapons against fake news.

During his testimony to Congress last week, CEO Mark Zuckerberg laid out the company’s three strategies for addressing misinformation. The first two include restricting spammers from purchasing ads and trying to leverage artificial intelligence to automatically delete accounts from state actors.

Lastly, Facebook is drawing upon independent fact-checking outlets to verify or debunk articles, photos and memes that users have reported. (Disclosure: Being a signatory of the International Fact-Checking Network’s code of principles is a necessary condition to be a partner.) And now, that project — which has had its ups and downs — is expanding beyond the West.

The latest additions to the program, which launched in December 2016 in the aftermath of fake news about the United States presidential election, include Mexico, Indonesia, the Philippines, India and Colombia — with more countries on the way. In 2017, Facebook’s partners were limited to the U.S. and three European countries: France, Germany and the Netherlands. Italy was added in January.

“We understand the false news challenge is very different in developing countries where people are coming online for the first time. The same solutions can’t be applied globally,” said Lauren Svensson, technology communications manager at Facebook, in an email to Poynter. “That’s why, in addition to scaling the third-party fact-checking program where we can, our focus to date has been on digital literacy.”

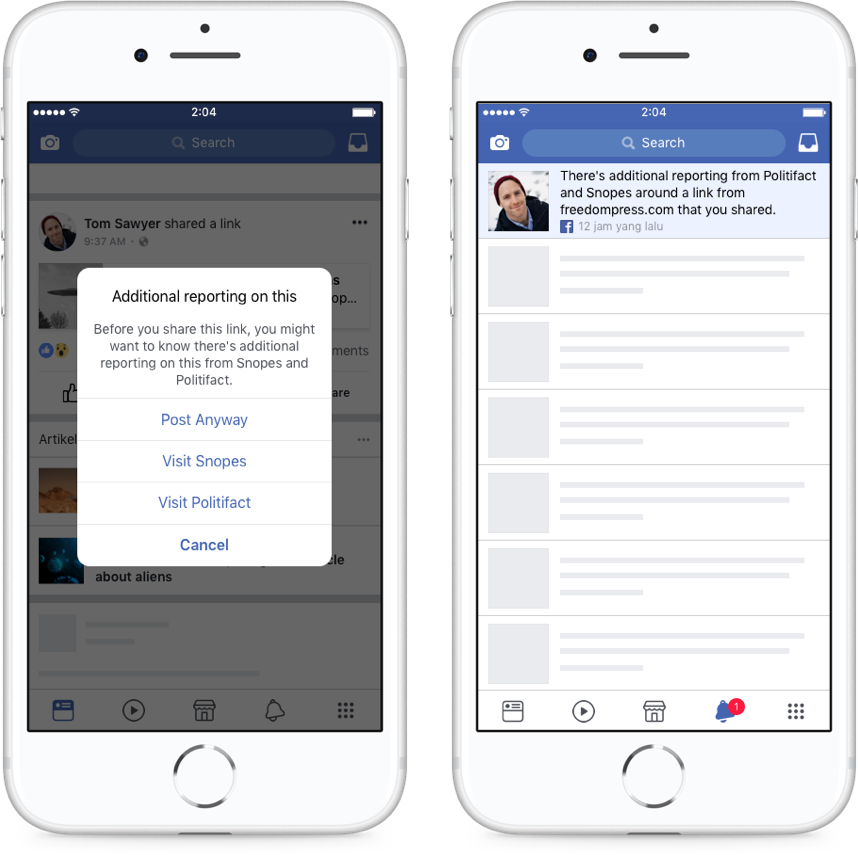

The additions come in regions that comprise the majority of Facebook’s active users. They also come amid a time of heightened scrutiny of Facebook’s fact-checking project, which decreases the reach of debunked stories in News Feed by a reported 80 percent, appends related fact checks, limits the visibility of misinforming pages and notifies users who share fake news.

Earlier this month, the Tow Center for Digital Journalism published a report on the state of the initiative, based on anonymous sources interviewed between August 2017 and January, which — while at this point outdated — provides some useful context for some of the project’s pain points in its first year of operation. At the same time, Facebook's tool’s efficacy and fact-checking’s ability to scale to misinformation has been questioned.

In spite of the criticism, the program is arguably Facebook’s most visible effort to combat fake news to date. And as it expands the project around the world, it’s becoming an increasingly iterative, sought-after tool in the effort to limit misinformation — particularly during upcoming elections.

“Facebook wields huge influence all around the world, often in fragile democracies where the consequences of manipulation and misinformation are very serious — more so even than in the U.S. and Europe,” said Peter Cunliffe-Jones, executive director of Africa Check, in an email to Poynter.

“The rollout of the fact-checking project to countries such Mexico, the Philippines and Indonesia is welcome but needs to go further.”

Mexico

The first expansion of the fact-checking program over the past month and a half was to Mexico in mid-March.

Ahead of this summer’s election, 60 publishers, universities and civil society organizations have united for a collaborative project called Verificado 2018, inspired by a similar project from September that popped up after an earthquake in Mexico City. As part of the initiative, which will focus on debunking fake news going into the July 1 presidential contest, Animal Político has been given access to the Facebook tool that fact-checkers like Snopes and Les Décodeurs have been using for months.

That tool shows partner organizations what users have flagged, as well as what’s going viral on Facebook. As compensation, Editor Tania Montalvo told Poynter that the company is paying Animal Político based on the number of hoaxes it debunks, with a maximum payment of $9,000 per month.

Montalvo said she expects the tool will help Verificado unearth some hoaxes faster in the run-up to the election but, as of now, it’s an incomplete solution.

“The thing that we see is that most of the electoral misinformation are images, videos or posts on Facebook,” she said. “The thing is, on Facebook, the fake news that actually have a lot of interactions are posts or images. We cannot report that on the tool — not yet.”

In March, Facebook announced that it would allow fact-checking partners to check viral images and memes, which were previously excluded from the tool in favor of linked stories. However, Montalvo said that change hasn’t yet made its way to Mexico, which Svensson said has about 82 million monthly active users — only Agence France Presse was using the feature as of publication.

And in her talks with the tech company, Montalvo said she hasn’t gotten a sense of when Animal Político will get the feature.

“Maybe that’s the first obstacle,” she said.

Indonesia

On April 2, Indonesia became the seventh country to be given access to Facebook’s fact-checking tool.

Misinformation on the social network has been particularly bad in Indonesia since elections in 2014 and 2017, said Sapto Anggoro, co-founder of the Indonesian site Tirto.id — Facebook’s local fact-checking partner. And he expects that the tool will have a significant impact on its dissemination.

Anggoro told Poynter in an email that, while he doesn’t have specific numbers, he’s seen plenty of misinformation on the platform while doing day-to-day fact-checking. And with elections a year away, Anggoro expects misinformation on Facebook — which Svensson said has about 115 million monthly active users in Indonesia — to get worse.

“Since main Indonesian media often use Facebook, the mis- and disinformation circulation through this platform will be high,” he said. (For an overview of the misinformation problem in Southeast Asia, read this.) “Mostly, the main topic is politics.”

At the same time, the government has taken a keen interest in regulating the spread of misinformation online. In January, the president appointed a chairman of a new agency to address “fake news on social media,” police have arrested members of different groups for spreading misinformation and authorities have been blocking specific accounts publishing content deemed harmful.

The platforms are increasingly playing a role in the region — even reportedly working with the government to tackle online hoaxes. By getting more access to potential misinformation on Facebook, Anggoro said his team will be able to fact-check more statements about the economy and politics before the campaign.

But, seeing how misinformation is a growing concern, he said hopes to see other Indonesian media outlets join in soon, too.

“It would have been better for the program to have been doing this in the past,” he said. “We hope, especially for Indonesia, that Facebook will have other partners for fact-checking.”

The Philippines

Facebook’s interest in Southeast Asia continues to grow — in a country whose government has taken a similarly hardline approach to misinformation.

Rappler and Vera Files announced their addition to the project last week — a move that has been lauded by lawmakers and criticized by a presidential spokesman. Both publishers will use the tool primarily to debunk fake news, which has increasingly been aimed at critics of the ruling party and the media.

In response to the news, some government supporters threatened to delete their Facebook accounts and move to other social media platforms, such as VKontakte. But Gemma Mendoza, head of research and content strategy for Rappler — which published an editor’s note in response to the criticism — told Poynter in a message that the move had generated little traction so far.

Regardless, the threat of misinformation has been growing for months in the Philippines, where Svensson said there are about 66 million monthly active users.

In February, the Newton Tech4Dev Network published a report that found public relations and advertising executives were among the “chief architects” of fake news in the country. Rappler itself was the target of a Facebook-enabled disinformation campaign that led to the revocation of its operating license. (President Rodrigo Duterte once even called the site a “fake news outlet.”)

“Information disorder in the Philippines is said to be worse than in other countries because of the existence, since the 2016 election, of a highly organized network of disinformation architects and the post-election recruitment of digital influencers and trolls engaged in the spread of disinformation by the Duterte government,” said Yvonne Chua, co-founder of Vera Files, in an email to Poynter.

“Beyond the political and ideological motivation, money and fame are a big lure. The situation has been aggravated by Free Facebook, which truncates and abbreviates posts, depriving users of full access to posts.”

In addition to PR and ad executives, the government itself has come under fire as one of the biggest purveyors of online misinformation. In February, a lawmaker drafted a bill to hold public officials accountable for spreading falsities, but a presidential spokesperson shot it down.

India

On Monday, Facebook announced a pilot launch of its fact-checking program in the Indian state of Karnataka.

Local debunking site BOOM will fact-check questionable posts on the platform. Managing Editor Jency Jacob told Poynter in an email is becoming a primary medium for misinformation in India, where Svensson said Facebook has about 217 million monthly active users — its largest market.

“Facebook is the medium that is connecting Indians on social media and with their friends and relatives around the world,” he said. “Also, unlike other countries, we have 22 official languages and thousands of dialects which makes it easier for misinformation to spread on any platform.”

The goal of BOOM’s addition to the project is to cut down on misinformation swirling about local elections May 12, Jacob said. But since it’s so last-minute, and seeing as how BOOM will only be able to fact-check English news stories, he’s unclear on whether or not it will have a discernible effect.

“It is too early to estimate if we can drastically cut down misinformation due to the limitations of scope and time with barely 25 days available to us,” he said. “But we hope to help Facebook and the fact-checking community in India to understand the steps that can be taken to battle this menace.”

Last week, BuzzFeed News reported that India is Facebook’s next problem area due to both the widespread presence of misinformation online and the importance of this year’s elections in determining Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s future. And the government itself has botched its own attempts to limit misinformation.

When asked if the company has plans to expand its fact-checking project to the rest of India — Karnataka accounts for only 4.8 percent of the country’s population — Svensson said that they are "starting small but do hope to expand beyond Karnataka." For Jacob, a successful pilot run would result in a limitation in the reach of at least some fake news sites.

“We hope to learn how fake news is created and disseminated by malicious players to unsuspecting users on Facebook,” he said. “If we can help in killing the distribution of some websites and pages through our work, that will be a good start for now in this pilot.”

Colombia

Like BOOM, Facebook’s newest fact-checking partners are rushing to debunk fake news weeks before a May election.

In an email to Poynter, Svensson said the tech company would roll out its fact-checking tool to both La Silla Vacía and Colombiacheck this week. Both publishers have been focused on addressing misinformation surrounding the May 27 presidential election.

"I think there has been an increase in the appearance not only of pseudo-informative websites but also that social networks and their users are playing a key role in the distribution of fake news," said César Molinares, a journalist at Colombiacheck, in an email to Poynter. "Now we are focused on the presidential campaign and we are going to investigate fake news not only in Facebook but other social networks."

Poynter reached out to both La Silla Vacía but had not heard back as of publication.

In Colombia, which Svensson said has 29 million monthly active users, misinformation is often political in nature.

Juan Esteban Lewin, a journalist at La Silla Vacía, told Poynter in October that the biggest fake news topics were last year’s referendum on a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the upcoming elections. Many hoaxes spread on WhatsApp — a messaging app that’s popular in Latin America for its limited data use, and one that’s pretty hard to fact-check on.

In January, President Juan Manuel Santos announced an "electoral intelligence unit" to curb potential cyber attacks from foreign powers and limit the spread of misinformation online. The Financial Times reported that fake news on messaging apps has taken aim at candidates across the political spectrum.

And Molinares said that he's seen people sharing false stories with the belief that they're helping inform their friends and family.

"More and more users of these networks are falling into the trap of giving credibility to this type of misinformation, with the aggravation that they are responsible for distributing them to their friends and family," he said.

Svensson declined to confirm which countries would be added to the program going forward. But future areas of interest for Facebook could be Brazil, where Facebook has invested R$550,000 (more than $165,000) in fact-checking projects ahead of the October general election, or Myanmar, where Chua said Facebook-specific misinformation is worsening the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Facebook is currently working with no countries on the African continent, and Cunliffe-Jones said that’s a problem seeing as several countries are battling forms of misinformation that have ramifications beyond mere political contests.

“It is incredibly important that this program is rolled out this year to key countries in Africa, where the consequences of misinformation can be so serious,” he said. “We know from the recent revelations that misinformation has been targeted at voters in Nigeria and Kenya in the past. And we know there are elections coming up early next year in South Africa, Nigeria and Senegal.”

But alongside expanding the fact-checking partnership to Africa, Cunliffe-Jones said that a lot more research is needed on the various effects and forms of misinformation around the world in order to develop responses that work for different countries. Because fact-checking looks different depending on where you are.

“The way that the public and policymakers access information, how it affects political processes and the impact that misinformation about areas such as health and civil society issues can have is enormous — and rarely looked at in studies in the U.S. or Europe,” he said. “Yet in some parts of the world, its effects are life-shortening.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated with comments from César Molinares, a journalist at Colombiacheck.