This is the first article in a three-part series on the people behind the misinformation phenomenon. Parts two and three will feature notorious fake news writers and prominent misinformation researchers.

DURHAM, North Carolina — Asa Royal missed the first day of the meeting because he was in class. On the second, he had to leave early.

But his project still interested a group of 48 fact-checkers, researchers and tech companies from four countries at an automated fact-checking conference organized by the Duke Reporters’ Lab in late March.

Royal’s tool, which he worked on with a three-student research team at Duke, sends American fact-checkers a daily email with fact-checkable claims from CNN by automatically parsing through the network’s transcripts using a tool called ClaimBuster. Bill Adair and Mark Stencel, co-directors of the Reporters’ Lab, showcased the feature on Royal’s behalf alongside other automated tools from Argentina and the United Kingdom.

Not bad for a 21-year-old.

“I’ve always been really interested in politics. I grew up watching the news — my most significant childhood memory is watching the (George W.) Bush-(John) Kerry debates,” he told Poynter in a phone interview before the conference. “When the chance presented itself for me to combine programming and politics, I was super happy to jump on it.”

Royal, a computer science major at Duke, started working with the Reporters’ Lab in fall 2016 after taking Adair’s news writing class. He was interested in journalism as a hobby or a potential career, and Adair had open positions for student assistants. (Disclosure: The Reporters’ Lab helps pay for the Global Fact-Checking Summit.)

For the first four months, Royal, a former reporting intern at the (Poynter-owned) Tampa Bay Times, watched and transcribed several hours of campaign ads each day in order to build a database of claims. That partially served as the later inspiration for the Tech & Check alerts — which he started programming last April.

Now, fact-checkers from The Washington Post and PolitiFact are using the alerts to publish stories.

“If there’s any beauty in the system, it’s that it removes the brute force element of some portions of reporting,” he said. “Nobody should have to watch all 15 hours of CNN to watch this one interesting claim that Ted Cruz made.”

Royal is one of several students around the world who are innovating at the forefront of misinformation, technology and fact-checking. Often working alongside political science and media researchers at some of the most prominent universities, these students are making serious contributions to our collective understanding of fake news.

From high schoolers to postdoctoral researchers, here are some of the students working on solving the problem of misinformation. Know someone you think we should know about? Email us at factchecknet@poynter.org.

Mihai Avram, Indiana University

Fake news isn’t all fun and games. But for Mihai Avram, it kind of is.

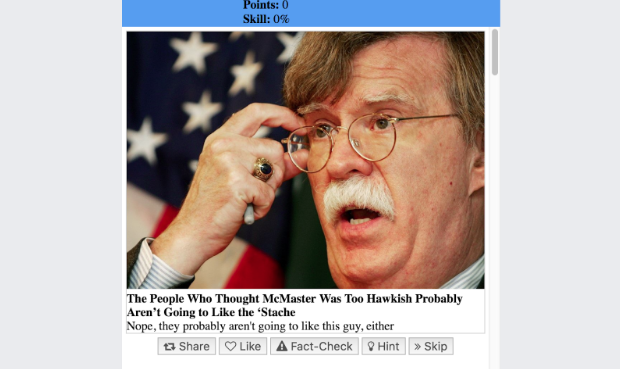

The Indiana University master’s student has developed a prototype for a game that allows users to decide whether or not to share, like or fact-check stories on social media. The game scores each action you take, giving top points if you share credible stories or fact-check dubitable ones.

Essentially, the game aims to increase users’ news literacy skills.

“Ideally, we would want to have a lot users play the game, nationally and internationally,” Avram, 25, said. “At the very least, I know journalists will definitely be interested because they’re the ones who are very curious about this new domain of trying to figure out, given these sources, what is real and what is fake.”

The game uses the News API to pull in different mainstream outlets. At the same time, Avram and his adviser, informatics and computer science professor Fil Menczer, pick fake news sources by leveraging Hoaxy, a tool that crawls social media and articles based on lists curated by fact-checkers.

While it’s still early to see how users are interacting with the game (Avram said most have just been helping him test that everything is working), most of the preliminary feedback has been positive. And that’s because it’s gamifying a complex problem, Avram said.

“We wanted to be creating a game that also has a purpose, so when you look at some of the most popular examples, such as the ESP game or even CAPTCHA,” he said. “You don’t really see them as games, but they definitely serve a purpose.”

Now, Avram is aiming to release an official website, as well as versions for iOS and Android devices. He said creating the game has surpassed his past class experiences and that, after graduating with his master’s, he’d like to pursue a Ph.D.

“The reason why I like it is for once I have the opportunity to create something that’s bigger than myself,” he said. “I want to be focusing on a lot of this stuff, and by ‘this stuff’ I mean social problems and being able to not only derive methodologies to solve this, but also create something that creates value in the world.”

Sreya Guha, Castilleja high school

It’s not just undergraduate and graduate students working in the misinformation space.

Sreya Guha, a 17-year-old senior at Castilleja — an all-girls high school in Palo Alto, California — spends her summers creating software like Related Fact Checks. The online resource allows internet users to paste links they doubt to see if it’s already been covered by a fact-checking organization.

“When you look at most news articles today, you find a row of social sharing buttons,” she previously told Poynter. “It would be great if, along with these buttons, when clicked, (one) would give users fact checks related to that article. The goal is to just illustrate that concept.”

The tool, which draws upon the ClaimReview schema (basically a few lines of code that help search engines recognize and surface fact checks), has attracted interest from technology companies like Google and Meedan for its sophistication. In addition to the online search, Guha created a Google Chrome extension and a transparent privacy policy. She even outlined the functionality for Related Fact Checks, as well as the problems it seeks to solve, in an academic paper.

In October, she presented the entire package at the International Semantic Web Conference in Vienna.

“After I did my research, I was looking for a bigger forum. While talking to family and friends, I heard about this conference,” she said. “I got to present my work to a group of computer scientists, which was a really nice experience.”

Despite the tool’s success, she said that, after graduation, she’d like to attend college and meld her interests in technology and journalism. Making a profit from tech companies doesn’t interest her.

“My intention wasn’t really to make a profit — it was just to introduce this idea,” she said. “I think it’s just good that that idea can be built upon and made better.”

Olu Popoola, University of Birmingham

Can we detect misinformation by using linguistics? Olu Popoola thinks so.

A forensic linguist and doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., Popoola has published research on detecting fake online reviews — which have become a major problem on shopping sites like Amazon.

“I found that online book reviewing has a certain form and conventions that are related to the genre, like mentioning both good points and bad points and justifying your rating,” he told Poynter in a message. “Most book reviews will follow this and the ones that deviate are likely to be deceptive.”

While his work is limited to book reviews on Amazon, Popoola, 45, said he’s now exploring whether or not applying linguistic norms to news articles and scientific papers could help journalists and researchers determine their veracity. He also runs deception detection workshops around the U.K. in which he shows participants “linguistic hotspots” — places where interviewees’ language can deviate from norms.

The goal: Prevent misinformation from making it into the mainstream press.

“My focus on ‘false news’ in particular comes from seeing the damage that media misinformation wreaks on lives first hand,” he said. “Nowadays, the ‘fake news’ problem is seen as an issue of clickbait created by foreign agents either for commercial or political gain. But the misinformation problem runs deep and goes back to established media outlets.”

Popoola first became interested in misinformation about four years ago while working on advertising research, in which he analyzed people’s speech and text patterns to see if he could predict a future sale or theft. He was working on a case of an alleged child abuse hoax at the time.

That work led him to the Centre for Forensic Linguistics at Aston University from 2015 to 2017, where he started researching deception and linguistics. He left to work at the University of Birmingham in October.

“And the rest is history,” he said.

Paula Szewach, Pompeu Fabra University

The impact of online misinformation is hotly debated. So how can we measure how much it actually mobilizes people to participate in politics?

That’s the subject of Paula Szewach’s master’s thesis, which she completed while studying political science at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. By using fact checks from Chequeado, a fact-checking outlet based in Buenos Aires, Szewach, 26, conducted an online survey experiment that measured how fake news mobilized people in Argentina.

“Democracy works on the assumption that the citizens need to be informed to make good decisions, so of course false information was always a concern for me,” she said.

What Szewach found was that respondents, who were all more than 18 years old and lived in Argentina, who were exposed to false political information online were more likely to sign online petitions or share things on their social media profiles than those who weren’t. No effect was measured on offline protests.

“Even when the evidence of my study is by no means sufficient to make a definite statement, it suggests that the influence of fake news might be to some extent overdimensioned,” she said.

Szewach had come across Chequeado prior to her research while working at the nongovernmental organization Asociación Civil por la Igualdad y la Justicia (ACIJ). That’s when she became interested in misinformation from a political scientist’s perspective — something she said is rather rare in the field.

“It seemed like an interesting topic to approach at the moment,” she said. “I think in my field, the problem in political science is that … political scientists don’t consider this to be a political science issue.”

While applying to Ph.D. programs at various universities, Szewach said that several people in political science departments asked how misinformation was relevant research instead of a cognitive sciences or psychology problem. She’s working to change that perspective, extending her master’s work to a proposal focused on disentangling “the mechanisms behind the effect of mis/dis information on political attitudes.”

And a big part of that is defining the problem in the first place.

“What I think one of the main challenges that this kind of research faces is that, for academic research, the definition of fake news is still very, very weak,” said Szewach, who hopes to do applied research for an NGO after she gets her doctorate. “It’s a problem because you need either to focus on a very restrained definition, which leaves out a big part of the phenomenon, or have a very elusive definition that is not really well seen in academic environments.”

“I think that students have an opportunity to present this as an actual academic political science.”

Jordan Urban and Adam Feldman, University of Cambridge and Warwick University

They started a promise-tracker at 17. Then they interned at Full Fact for three months while finishing their last year of high school.

Now 18, both Adam Feldman and Jordan Urban authored a report for the British fact-checking charity on the future of promise-tracking — one of the predominant forms of political fact-checking around the world. Based on an analysis of existing promise-trackers around the world, it starts with some general principles and builds toward some recommendations for building promise-trackers.

“Part of the reason that Adam and I wrote (“The Future of Promise Tracking”) while at Full Fact was because we weren’t sure how sustainable running GovTracker would be for us, and were desperate to get on paper our advice for anyone looking to replicate and improve upon our work in the U.K. and across the world,” Urban told Poynter in an email.

Feldman, who will start at Warwick University in the fall, told Poynter in an email that he first became interested in misinformation during the 2015 election in the U.K.

“I was getting tired of constantly getting into conversations with friends and family that ended with ‘they’re all liars,’” he said. “Misinformation ruined positive political discourse for me just at the time I was beginning to grapple with political issues.”

He and Urban developed Government Tracker, which they had the idea for while discussing Trudeaumeter, a Canadian promise tracking site, in the lunch line at school. Urban, who will start at the University of Cambridge in the fall, said that, while they largely stumbled into promise-tracking by accident, both he and Feldman plan to continue working in the misinformation space as long as they can.

“To give people access to the policies of the government in full, in a simple way, provides an important service,” said Urban, who is co-authoring an academic paper connected to “The Future of Promise Tracking” project. “People can actually see what the government was voted in to do, rather than having an idea of the gist of their policies, with detailed knowledge of a couple thrown in.”

Urban said that young people can bring new perspectives to the misinformation space because they’ve grown up with the internet in their pockets. Feldman agreed, but said that he’s learned more from the fact-checkers at Full Fact than the other way around.

“It would be easy for me to say that my growing up with technology makes me much more adept at dealing with this issue since it is so internet driven,” he said. “However, from my experience of the last two years, the guys that are tackling this issue have far greater experience and technological expertise than me.”

“I do know meme culture a lot better though! That does actually help a lot (sometimes)!”