Bobby Duffy knows how wrong we all are.

In the six years that he’s overseen IPSOS Mori’s “Perils of Perception” studies, Duffy has documented the enormous gap between facts and public perceptions on topics like immigration, public health and criminality.

For instance, across almost 40 countries surveyed for his studies, the public grossly overestimates the share of teenagers giving birth each year. Brazilians lead the pack, with an average guess of 48 percent of girls ages 15 to 19 giving birth each year against an actual figure of 6.7 percent.

But estimates are way off across the board, with most respondents thinking anywhere between 1 in 10 and one in two teenage girls were having a baby each year.

Similar patterns hold for how many people think prisoners are immigrants, as well as estimates of the wealth owned by the top 1 percent and the public health budget. We’re even wrong about how wrong we are, with large minorities of respondents confidently answering that they thought they got all answers correct when clearly, they did not.

In a phone interview and in his newly-published book (“The Perils of Perception: Why We Are Wrong About Almost Everything”), Duffy, now the director of the Policy Institute at King’s College London, attributes these misperceptions to three interrelated factors: biases, identity politics and the media.

Biases on prominent display in the “Perils” surveys include the tendency to think things are worse than they actually are, as with teenage birth rates, or to look at the past with what Duffy calls “rosy retrospection,” as with estimates of the trend in murders.

We also generalize from our own experience — something most evident from Indian responses on internet penetration. Survey guesses that 64 percent of India’s population was on Facebook and 60 percent on the internet when the real figures were 8 percent and 19 percent respectively were likely informed by the fact that the poll was conducted online — respondents thought most people were like themselves.

The media and identity politics also play their part. Right-wing UKIP voters in Britain overestimated immigrant numbers more than left-wing Liberal Democrats. Headlines on mass immigration result in greater fluency with the phenomenon.

And sometimes it’s just a question of our brains struggling with large numbers.

“People often think ordinally rather than in precise percentages,” Duffy said. With numerical guesses, responses are expressions of general amounts rather than legitimate estimates that could be defended. “It’s like saying ‘a lot’ or an ‘awful lot’”.

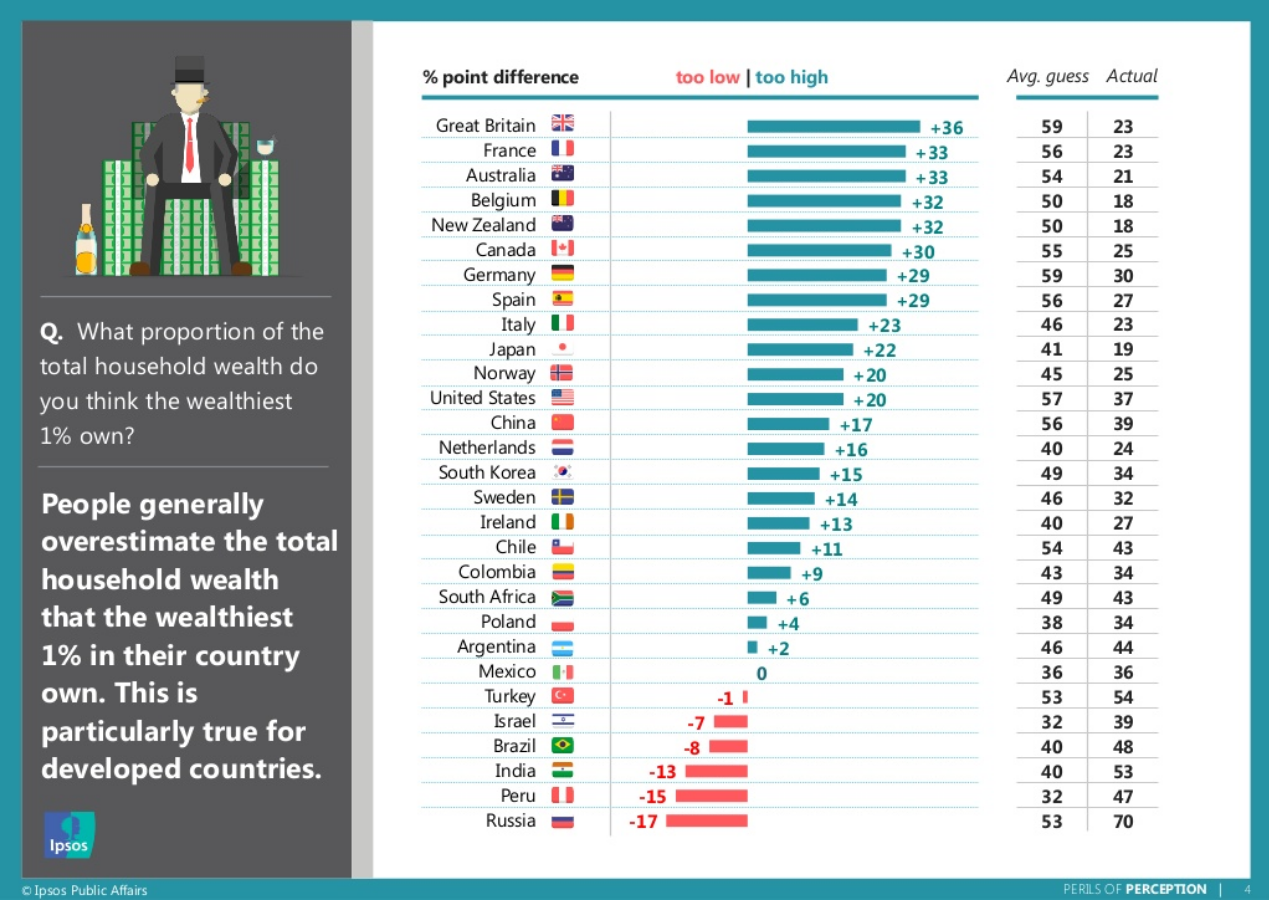

One of the most striking examples in the book concerns what percentage of wealth we believe is held by the top 1 percent.

French respondents thought the top 1 percent of households owned 56 percent of all wealth. When asked how much they should own, the average response was 27 percent. But the actual figure was 23 percent, and the (incorrect) implication one could draw is that most French people want the rich to get a little bit richer.

Both survey figures are wrong but their proportion is probably right. Respondents aren’t just making a numerical guess, they are signaling in broad strokes that the rich are rich and should be less rich.

Despite our systematic and unabashed wrongness, Duffy hasn’t fallen prey to the sirens of “post-fact.” He thinks our condition is neither new nor intractable.

First, novelty. Americans were wrongly guessing that the unemployment rate was 32 percent in 2014 — one of many wrong numbers Donald Trump later used in his famously false claims about unemployment.

Perhaps more important, Duffy’s instinct in looking at these figures is not to throw his hands in the air, shruggie-style.

“While I talk a lot about our biases and identity politics in the book, I also make the point that we are not automatons. We are not slaves to these biases,” Duffy told me over the phone.

Solving the problem — because it’s a problem when anywhere from 8 to 44 percent of online populations surveyed erroneously believe there is a tie between vaccines and autism, for instance — requires an accurate diagnosis.

And that means calling these wrong beliefs “misperceptions,” as Duffy does, rather than “ignorance.”

“Misperceptions are positively held incorrect views,” he said, “where ignorance is just the absence of knowledge on a particular piece of information.”

Drawing this distinction matters because misperceptions are not “a blank slate to write on or a vessel to fill up with knowledge,” Duffy adds.

Where does this leave fact-checkers, and other journalists trying to communicate the key facts around some of these widely held misperceptions?

NEWSLETTER: Sign up for The Week in Fact-Checking

Duffy thinks fact-checkers should go beyond just relaying the facts. Reducing misperceptions isn’t just about ensuring accurate information is available — it’s about explaining where it comes from in the first place. What element of media coverage might people believe terrorist deaths have increased since 2001 rather than decreased? What elements of our thinking might have led us to throw a large number at a more contained phenomenon? What about the actual facts of our own life, family situations and local communities makes us generalize to a society-wide misperception?

These are all questions that should find an answer in a complete fact check.

Tone is everything. Most people don’t mind learning a new fact. But most people do mind feeling stupid about it. Fact-checking must not come across as haranguing and must be cognizant of the fact that we all suffer from the same biases and deploy the same mental shortcuts.

Repetition will also have to be a part of the solution. A 2017 study has found that repetition helps us become more familiar with facts, not just with falsehoods. This might mean publishing fewer fact checks but crafting the important ones more effectively and bringing them to a larger audience.

The key question about how to fact-check these topics should be “more about how you do it than whether you do it,” Duffy said.

Duffy has also found that more dialogue helps. At IPSOS, he helped conduct focus groups and deliberations on what he admitted could be “very, very dull” topics like how legislation is made. And what he found was “people were engaged and not dogmatic and were shifting their views.”

Fact-checkers are increasingly looking at ways to increase the dialogue with their audience, whether it be by holding town halls or literally doing the fact-checking on the streets.

“They don’t shift their entire worldview, but they listen to evidence and some people do change their opinion,” Duffy said. That echoes several recent studies on the effect of fact-checking.

In the end, Duffy thinks we can combat our misperceptions most effectively by following the late Hans Rosling’s “Factfulness” approach.” He characterizes this as both being more thoughtful about how we think and ensuring there are some key facts we are fluent in.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Rosling’s Sweden performs relatively well in IPSOS’ “misperceptions index” — in 2017, Swedes were the most accurate in their guesses but among the least confident about their accuracy. There’s a takeaway.