It’s tough out there for college students these days — especially on their news feeds.

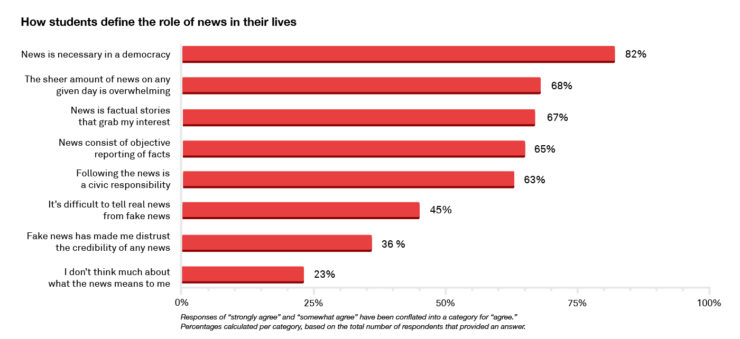

According to a new media consumption study, almost half of the nearly 6,000 American college students surveyed said they lacked confidence in discerning real from fake news on social media. And 36 percent of them said the threat of misinformation made them trust all media less.

“Our report suggests that in some ways, we have created for young people an extremely difficult environment of news. We need to figure out ways to guide them so they can navigate it,” said John Wihbey, a Northeastern University professor and one of the study’s co-authors, in a press release. “The rather contentious and poisonous public discourse around ‘fake news’ has substantially put young news consumers on guard about almost everything they see.”

In addition to student surveys at 11 American universities, the year-long report — which was commissioned by the Knight Foundation and published by the nonprofit Project Information Literacy — analyzed posts from 135,000 college-aged Twitter users to learn more about their media consumption habits. Researchers found that students often cross-reference their news with several different sources because of the possibility of misinformation.

While that finding points to college students’ proclivity to confirm news and information before they share it, Wihbey said in the release that it’s also concerning for trust in the mainstream media.

“That’s a double-edged sword because on the one side, you’re arming young news consumers to be aware of the source of information,” he said. “On the other side, we don’t want to raise a generation not to believe in the power of well-reported, well-researched, well-sourced news.”

Project Information Literacy's findings add a qualitative dimension to what researchers have already found about the ability of college students to detect misinformation online.

In November 2016, Stanford University published a study that found students of varying levels were consistently unable to determine the credibility of an online news source. The report was based on more than 7,800 responses from middle school, high school and college students in 12 states who were asked to evaluate information in tweets, comments and articles.

According to the report, when middle school students were asked to distinguish between an ad and a news story, they often couldn’t. High school students did not consistently notice that a chart on gun violence was created by a political action committee and college students did not go out of their way to research sites with .org URLs.

RELATED ARTICLE: What we learned about media literacy by teaching high school students fact-checking

“Overall, young people’s ability to reason about the information on the internet can be summed up in one word: bleak,” the researchers wrote. “Our ‘digital natives’ may be able to flit between Facebook and Twitter while simultaneously uploading a selfie to Instagram and texting a friend. But when it comes to evaluating information that flows through social media channels, they are easily duped.”

Mike Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University at Vancouver, told Poynter in a message that the Project Information Literacy study backs up a lot of what he’s found to be true about students’ media literacy.

“Students feel overwhelmed and disempowered; they want to live up to a standard of truthfulness that they feel has been made impossible by the firehose; they tend to overestimate the amount of fake news that reaches them, and are alternately gullible and cynical,” he said.

The report also reveals a key sticking point for Caulfield: Students do care about truthful news. It’s just that the current media ecosystem makes it hard for them to determine what that looks like.

“I'm glad to see this report because often I have these conversations with adults that assume the big problem is getting students to care, because often students have very cynical postures. But those cynical postures are based on being overwhelmed, and once you give them quick tools they can apply, the cynicism goes away,” he said. “Students opt out of using truthfulness as a primary criteria because they think finding the truth is a 20-minute process.”

Disclosure: The Knight Foundation is one of Poynter’s largest funders.