ROME — Snopes. Full Fact. Chequeado. Teyit. Africa Check.

Chances are, no matter where you are, you know at least one of these fact-checking outlets — or perhaps another of the 144 similar projects around the world. But do you know what their finances, organizational structure and staff look like?

In occasion of the kickoff of its fifth annual Global Fact-Checking Summit, the International Fact-Checking Network published a report today that takes a look behind the curtain of several different fact-checking projects around the world. The fact sheet, which is public on Google Drive and based on a self-selected survey conducted between April and May, includes 42 of 57 signatories of the IFCN’s code of principles. All those surveyed are attending Global Fact.

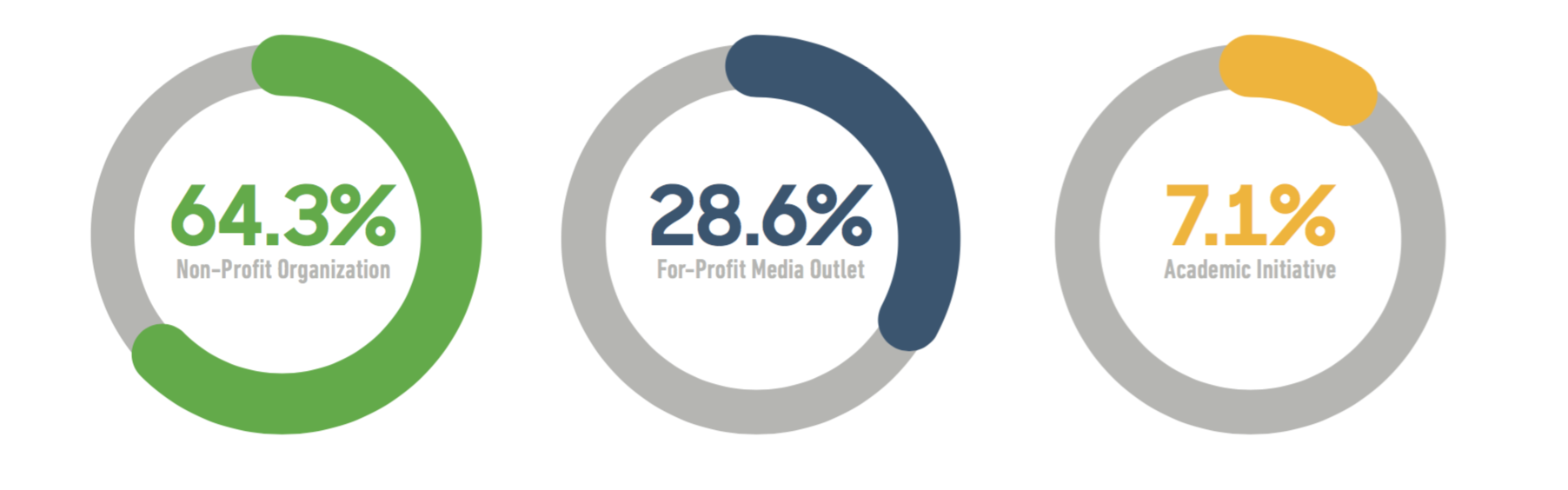

Among the headline findings of the report: The vast majority of fact-checking projects are nonprofit organizations or affiliated with a university. They’re also almost all digital-first, with 41 respondents saying they publish primarily online, with the exception of Spanish TV show El Objetivo de Ana Pastor.

“The latest data collected by the IFCN echo previous surveys showing that, globally, the fact-checking field is dominated by small, mission-driven nonprofits operating with limited resources,” said Lucas Graves, a senior research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, in an email to Poynter. “What the data don’t show is the challenge faced by independent NGO- or university-based fact-checkers — even some leaders of the global movement — in building up a sizable audience.”

Aside from structure and distribution, fact-checking organizations tend to be newer. More fact-checkers launched in the past two years than in the previous decade, with eight starting up in 2017 alone.

While that exaggerates the frequency of recent projects, since defunct outlets aren’t included, it’s in line with the growth that the Duke Reporters’ Lab has seen in recent years. (Disclosure: The Reporters’ Lab helps pay for Global Fact.)

Another key finding of the report is that, while viral misinformation continues to gain ground on platforms like Facebook, fact-checking projects employ relatively few people. The 42 outlets surveyed have a cumulative 229 employees in 28 countries — or about six people per organization.

Finally, the report takes a look at the budgets for each fact-checking project. The majority (62 percent) operated with less than $100,000 in 2017, while a sizeable portion (19 percent) had more than $500,000.

That doesn’t capture the different purchasing power in the countries surveyed. And in the future, Graves said he’d like to see more survey work done on ad hoc efforts to fact-check political claims — particularly on TV.

“We need to know a lot more than we do about fact-checking efforts attached to regional or even local newsrooms around the world, especially in broadcast,” he said. “These efforts come and go with campaign season. They don’t attend Global Fact, and they’re hard to track even for Duke’s impressive census. But collectively they may represent much or even most of what people experience as political fact-checking, and it's important to understand how they operate.”