With one hurricane barreling toward the East Coast and two more swirling in the Atlantic Ocean, Americans are bracing themselves for another round of dangerous tropical weather. And with that comes a potential influx of misinformation about the storms.

Hurricane-related hoaxes are among the most popular types of misinformation on social media, in part due to the fact that they’re breaking news stories. Hoaxers use the uncertainty of the situation and people’s volatile emotions to try and get them to share misinformation, which they often do since people may check social media more during a natural disaster.

Fake weather maps have gone viral on social media in the lead-up to hurricanes. People too often fall for the same fake photo of a shark swimming on a freeway. And someone will inevitably tell those in the path of a storm to store their valuables in the dishwasher — which is not necessarily safe.

While some of them are funny, those kinds of hoaxes can have dangerous consequences ahead of tropical storms. Manipulated weather projections could cause panic in areas where there is no chance of a hurricane and bogus safety tips could jeopardize people’s storm preparation.

So here’s a list of 10 tips to help both news consumers and journalists avoid spreading misinformation about hurricanes online. Have another tip you think should be included here? Email dfunke@poynter.org.

1. Get your weather information from the National Hurricane Center and the National Weather Service

The National Hurricane Center, a division of the National Weather Service, publishes updated forecasts and projection models at regular intervals both online and on social media. The NWS itself is another good source for up-to-date hurricane maps and evacuation notices — do yourself a favor and follow both on social media so you don’t miss a thing.

2. Know a few basic facts about hurricanes

This may seem obvious, but in the past, there have been false reports that hurricanes were upgraded to Category 6 storms due to their strength — a classification that doesn’t exist. There are several other facts about hurricanes that everyone should know to avoid falling for such fakery.

First, the point of a cone map isn’t where the center of the storm will be, just where it’s most probable at the time. Everything within the cone represents where the center of the storm could go based on forecast errors over the past five years, not how big the storm is.

You're probably hearing a lot about "the cone". So what does that really mean? Check out this graphic about understanding the forecast cone. Remember, impacts can occur well away from the center of the storm! #scwx #gawx pic.twitter.com/GYnaZvS2BV

— NWS Charleston, SC (@NWSCharlestonSC) September 10, 2018

Second, the NHS will never definitively say what the path of a storm is more than a few days out. Beware of claims that prematurely say a hurricane will definitely hit or avoid your area.

Third, categories don’t necessarily denote the level of a danger a hurricane poses, just the speed of the winds it carries with it.

That’s by no means an exhaustive list, but keeping those facts in mind when you’re consuming or producing news to avoid falling for misinformation about hurricanes.

3. Don’t believe everything a spaghetti plot shows you

We’ve all seen them countless times during the buildup to big storms: messy maps of the Atlantic Ocean with thin, colored lines extending out and up toward the U.S. But what do they mean?

It depends, but usually not much.

Last year, Ars Technica published a piece criticizing a South Florida Water Management District spaghetti plot Nate Silver shared that showed the potential routes Hurricane Irma could take around Florida. The key problem with that lied in the data sources used to draw the lines.

Still some uncertainty in the Hurricane Irma forecast but more and more projections are converging on Florida. https://t.co/Tk8G06vz0g pic.twitter.com/ADFYTHTsdG

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) September 6, 2017

While some of the plot's data sources were useful, some of them were out of date by 12 hours or simply unrelated to tracking a storm’s path through the Atlantic. When assessing hurricane projections online, it’s better to stick to data provided by the NHC.

4. Use a reverse image search

This is a classic and easy one — and among the fastest ways to debunk a viral image.

If you see an image on social media that seems too wild to be true, such as a shark swimming on a freeway in a major city, take a second to double-check its validity. If you’re using Chrome, simply right click on the photo and select “Search Google for Image,” then see where else it has been published. You can also upload photos to the Chrome smartphone app.

Two other useful tools you can use to double-check a photo include RevEye and TinEye. The former is a Chrome plugin that allows you to search multiple engines at once, while the latter is a search similar to Google's. If a photo is widely cited for a different event, or if a fact-checker has already debunked it, hold off on sharing — your followers will thank you.

5. Be wary of claims about record-setting storms

During hurricanes, news often starts circulating that the storm is the worst, biggest, deadliest or most erratic ever recorded. But whenever someone makes a hyperbolic claim about a hurricane, that’s something to watch out for.

Even when a storm is within 24 to 36 hours from arriving, there’s still so much even meteorologists don’t know. While people should take the hurricane seriously, they should also steer clear of those looking to incite panic.

6. Watch out for false narratives, jargon and rushes to judgment

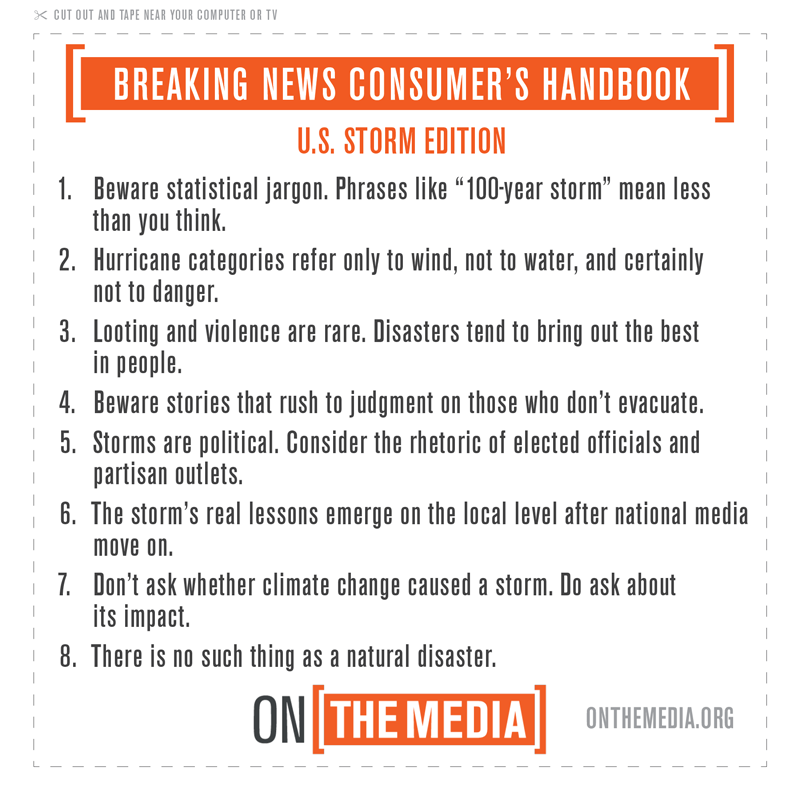

This one comes from WNYC’s On the Media. Last year the podcast discussed some of the things journalists get wrong when covering storms like Hurricane Harvey, and how to fix them.

Some of the important points made during the podcast include the importance of avoiding statistical jargon like “100-year storm,” remembering that looting and violence are rare in the aftermath of hurricanes and recognizing that all storms are inherently political.

OTM also published a version of its breaking news handbook specifically about U.S. storms. While it’s catered to journalists, it provides a good framework for news consumers to use when trying to interpret news about hurricanes.

7. Don’t assume everyone in the path of the storm needs to evacuate

A common misconception during big hurricanes is that people who stayed behind ignored evacuation orders, and they’re often judged for doing so. But not everyone in the path of a storm needs to leave — especially just because of its category.

It’s important for people in the path of hurricanes to listen to their local officials to know when and whether or not to evacuate instead of media outlets and friends. They can go to their official county website to see if they're under an evacuation order.

For those outside the storm path, keep in mind that evacuations are based on a myriad of things, from the elevation and flood risk of an area to the mobility and needs of those who live there.

8. Fact-check viral social media videos

Just like with photos, social media users will often take past storm coverage out of context and publish it under a new, false context in order to get attention. InVid, a browser extension, lets you paste a Twitter, YouTube or Facebook link to a video and then parse out its keyframes. Then, you can run a reverse image search on them using the tools in tip No. 4 to see where else the video appears online. If you’re on a phone, try screenshotting the video and searching Google for it using the Chrome app.

If that content is taken out of context, you’ll likely find it elsewhere, such as in a news article about a past storm. If you don’t find anything, don’t assume it’s true by default — slow the video down and check out the frames for anything fishy. As always, if your gut tells you something is off, don’t share it.

9. Approach every post and update with skepticism

This is perhaps the most important thing to remember during hurricanes — and no one is exempt.

Look out for misinformation that comes from politicians and public officials; sometimes they will amplify rumors they found on social media before receiving confirmed information. Don’t always take your local meteorologist or even national journalists at face value, since they’ve been known to share misinformation during storms too — always confirm updates with your local NHC or NWS branch.

And, obviously, analyze social media profiles’ ages, bios, links, following lists and prior posts to determine whether they’re authentic. Here’s a good tool for doing that on Twitter, and here’s one for Facebook.