It’s hardly a secret that news deserts are spreading, but just how bad is it?

A comprehensive new study released today by the University of North Carolina’s School of Media and Journalism shows that far more U.S. communities have totally lost news coverage — more than 1,300 — than previously known.

Top findings:

- About 20 percent of all metro and community newspapers in the United States — about 1,800 — have gone out of business or merged since 2004, when about 9,000 were being published.

- Hundreds more have scaled back coverage so much that they’ve become what the researchers call “ghost newspapers.” Almost all other newspapers still publishing have also scaled back, just less drastically.

- Online news sites, as well as some TV newsrooms and cable access channels, are working hard to keep local reporting alive, but these are taking root far more slowly than newspapers are dying. Hence the 1,300 communities that have lost all local coverage.

“The stakes are high,” the researchers say in their report. “Our sense of community and our trust in democracy at all levels suffer when journalism is lost or diminished. In an age of fake news and divisive politics, the fate of communities across the country — and of grassroots democracy itself — is linked to the vitality of local journalism.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Report for America is ready to kick growth into a higher gear

Comprehensive, searchable database

UNC’s startling statistics arise from a comprehensive new database created by its researchers. With publication today of their report, "The Expanding News Desert," the database became available to all to search, down to the county level, at usnewsdeserts.com.

The 14-member research team, composed of four full-time researchers and 10 graduate and undergraduate students, first melded data in differing formats from almost 60 national, state and regional newspaper organizations as well as from the Local Independent Online News Publishers, or LION. They then overlaid the result with demographic, political and economic data from government sources.

A preliminary analysis in May showed that at least 900 communities had lost all news coverage since 2004. Penelope Muse Abernathy, the Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at UNC who directed the year-long study, said in an interview that no work she had ever undertaken had spurred so much response as the earlier finding.

Then her team used internet research and interviews to resolve conflicts and ambiguities in the data, some of which was out of date and some of which was ambiguous because different sources kept data in different ways. This led to today’s announcement of more than 1,300 news desert communities, supplemented with stories of many publications and communities that epitomize the trend.

“This is more than baseline data,” Abernathy said. “It shows the scale and scope of the problem and allows us to concentrate on places that are most at risk.”

She said researchers will continue to update the database as long as funding is available. She said the Knight Foundation and UNC jointly funded the effort, which is the latest in a growing stream of academic efforts to understand and overcome the withering of community news coverage. A few examples:

- In August, a Duke University study took an approach that’s very different from UNC’s and found a different kind of bad news. It analyzed all the news stories provided to 100 randomly selected communities in the same week and discovered that only 17 percent were about the community where they were presented.

- The Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University, which has historically focused on national and global mainstream news, has recently added a focus called Digital Journalism: Sustainability & Business Models. “As traditional newsrooms shrink and even disappear,” the Shorenstein website says, “the information landscape for Americans is bleak.”

- The Center for Cooperative Media explored the factors that make for-profit online publishers successful by interviewing the publishers of 43 sites and found that 1) "Only the wealth of the community is statistically correlated with ‘success’” and 2) "It seems clear that outside support is crucial to ensure that local news outlets can be sustained in poorer communities.”

- And at Ohio University, professor Michelle Ferrier, director of the Media Deserts Project and a pioneer in studying fading newspapers and online efforts to replace their journalism, went beyond research and announced the launch of ZipIt.news as communications hubs to serve 20 rural communities in southeast Ohio.

Extent of the desiccation

About 70 percent of the newspapers that have died since 2004 were in suburban areas of metropolitan areas that historically offered many news choices, the researchers say, but counties with no coverage at all tend to be rural.

State and regional papers have also pulled back dramatically, and this “has dealt a double blow to residents of outlying rural counties as well as close-in suburban areas.”

Compounding this, most emerging online news sites are clustered in affluent metro areas, and only two are in counties that have no newspaper.

Further, the people who live in news desert communities tend to be poorer, older and less educated than the average American — often its most vulnerable citizens, the researchers say.

“If journalism and access to information are pillars of self-government,” said Duke University professor Philip M. Napoli after leading a separate study of three demographically disparate communities in New Jersey, “these tools of democracy are not being distributed evenly, and that should be cause for concern.”

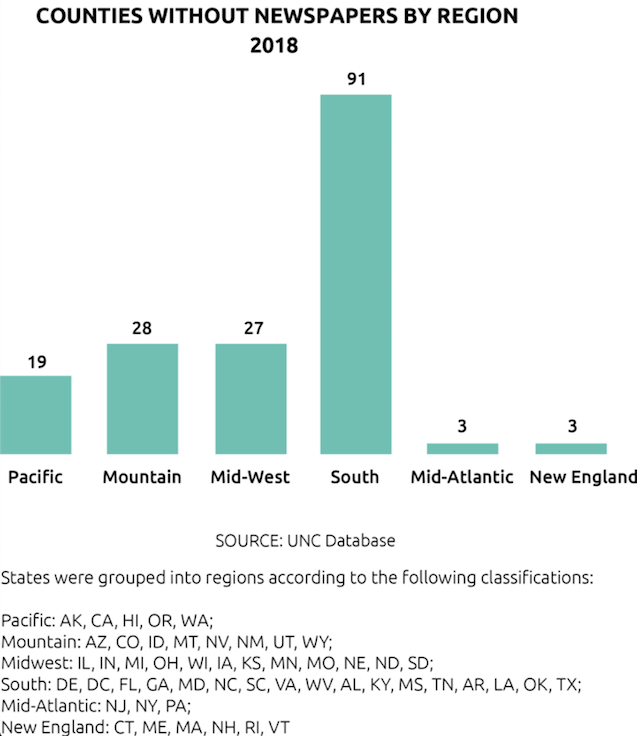

When the UNC researchers finished their database, it showed that of the 3,143 counties in the United States, more than 2,000 now have no daily newspaper, 1,449 have but one newspaper of any kind, and 171 counties, with 3.2 million residents in aggregate, have no newspaper at all.

And the database may overstate the number of surviving standalone papers. The researchers estimate that 10 to 20 percent of the papers in it are geographically zoned weekly editions published by metro dailies. Papers owned by Digital First Media number 158 in the database, for example, but Digital First’s website lists fewer than 100. Different industry databases list zoned editions in different ways, making them difficult to count accurately.

As print publishing continues to wither, the researchers predict, many zoned editions will become ads-only shoppers or specialty publications, or be eliminated entirely.

Ghosts stalk news deserts

The NewsGuild-CWA credits Abernathy with coining what it calls the bleak metaphor of ghost newspapers. In an article in March, the union describes these ghosts as “pared-down-to-nothing papers (or even single-page inserts) that are the remnants of once-robust local publications.”

“The quality, quantity and scope of their editorial content is significantly diminished,” the UNC report says of the ghosts. “Routine government meetings are not covered, for example, leaving citizens with little information about proposed tax hikes, local candidates for office or important policy issues that must be decided.”

The researchers identify two common ways newspapers become ghosts:

1. A larger paper buys a smaller one in a nearby community and the smaller one slowly fades away as the titles merge their coverage efforts. The researchers discovered that almost 600 once-standalone newspapers — or one third of the 1,800 papers that the country has lost — had became advertising supplements, free distribution shoppers or lifestyle specialty publications. “In its final stages of life,” the report says, “there is no breaking news or public service journalism.”

2. Owners cut their news staffs so drastically that a newspaper cannot adequately cover its community. The researchers say this tends to happen at dailies and larger weeklies and estimate that 1,000 to 1,500 of the 7,100 newspapers still publishing have cut more than half of their newsroom staffs since 2004.

The researchers say the ghosts include metro papers such as The Denver Post and state and regional dailies such as The Wichita Eagle; both have cut staffs and pulled back their coverage dramatically.

Six hundred weeklies that evolved into advertising supplements were removed from the UNC database, but researchers kept the 1,000 to 1,500 titles with drastically reduced editorial missions that still provide some value. “The sheer size of this contingent,” the report says, “speaks to the magnitude of the diminishment of local news in recent years.”

Valiant efforts, looming threats

The researchers tip their hats to news entrepreneurs who have started online journalism efforts, often laid-off journalists who are driven to continue coverage of their communities, and to resourceful TV news departments and public access cable channels.

LION, the association of online publishers, estimates that there are 525 local digital sites across the United States, some for-profit and others nonprofit. About two-thirds, the UNC researchers say, offer coverage of government, politics, business, sports and lifestyle features, similar to community newspapers’ coverage. The others cover state and regional issues or focus on single niche topics.

This is not an easy path. A 2015 survey by The Los Angeles Times found that one in four online sites had failed. A 2016 Knight-sponsored analysis of 153 online sites concluded that only one in five attracted enough visitors and funding to be self-sufficient. UNC says its analysis of local news sites identified by LION revealed a similar pattern.

Most online news efforts, the researchers said, are located in affluent communities where residents have multiple media options.

Most online sites have launched in the last decade. But in some communities, older media are stepping up. Studies have found that regional TV newsrooms tend to focus on soft features, crime, weather and sports, and rarely report about community-level civic life. But some are much more ambitious. The UNC researchers cite a Knight Foundation study of television news, released in April, that found stations from Hawaii to Idaho to Virginia that offer robust local news reports.

The researchers also quote an official of the Alliance for Community Media, which lobbies on behalf of local cable access channels, as saying there are big differences in their effectiveness from state to state and community to community. The UNC report cites effective cable access efforts in the outer boroughs of New York City and in New England.

Despite these efforts, dark forces loom.

The UNC report updates its 2014 study on ownership of newspapers, which showed that hedge funds and private equity firms own vast swaths of the newspaper landscape — and that they have essentially no interest in anything but their profit margins. This makes them more prone than independent publishers to merge or close papers that don’t meet their profit requirements.

And newspapers have been withering at an alarming rate during the longest economic expansion in our nation’s history. What will happen when the next recession breaks?

Last December, Matt DeRienzo, executive director of LION, addressed this question in a piece for Nieman Lab looking ahead to the new year we’re now living:

“The last recession was brutal for newspapers and local news. The next one could be an extinction-level event.”

In an essay that closes their report, the UNC researchers urge a concerted effort to counteract this dire trend and end with a quote from Abernathy’s April testimony before the Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy:

“The fate of communities and local news organizations are intrinsically linked — socially, politically and economically. Trust and credibility suffer when local news media are lost or diminished. We need to make sure that whatever replaces the 20th century version of local newspapers serves the same community-building functions. If we can figure out how to craft and implement sustainable news business models in our smallest, poorest markets, we can then empower journalistic entrepreneurs to revive and restore trust in media from the grassroots level up, in whatever form — print, broadcast or digital.”

Correction: This story has been modified to correct Philip M. Napoli's current position. He is now at Duke University.