Facebook is ramping up its efforts to cut down on misinformation ahead of Brazil’s election this fall — and a right-wing movement is protesting.

On Wednesday, the technology company announced that it had removed a network of 196 pages and 87 accounts in Brazil that violated its authenticity policies “after a rigorous investigation.” The move came less than a month before the campaign for the October general election kicks off.

“These were part of a coordinated network that hid behind fake Facebook accounts and misled people to sow division and spread misinformation,” reads a blog post on Facebook’s site. “The accounts and pages we took down were in direct violation of our policies.”

Following the news, which was widely reported in the national media, far-right organizers gathered outside Facebook’s office in São Paulo to protest the decision to remove the pages. Which pages were removed was not included in the company’s press release, but Reuters reported that the network’s pages had amassed about half a million followers — many of them members of the right-wing movement Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL).

A Facebook spokesperson told Poynter that the targets of its investigation were willfully spreading misinformation on a network of fake accounts and pages, some of which were created by real pages. They said among the accounts removed were two prominent right-wing figures who were involved in the network: Renan Santos and Renato Battista.

“What we determined is that those accounts and pages were directly connected and directly involved in a policy violation we call coordinated inauthentic behavior,” said the Facebook spokesperson. “Basically when a group of people use fake accounts to create pages that are used to spread fake news and use real accounts to amplify and reproduce and viralize that misleading content — and they do that in a coordinated way — that’s against our policies.”

That’s different than Facebook’s other fake news policies, which don’t allow for the removal of content simply because it’s wrong. Misinforming pages are allowed to exist on the platform as long as they aren’t inauthentic and don’t violate other community standards — although Facebook has been more reticent to remove such pages in the U.S.

The Facebook spokesperson said the move was not an attack against the right, and that they would take similar actions against any partisan groups that use inauthentic accounts to spread misinformation. The spokesperson couldn’t speak about any other ongoing investigations, including whether or not they were looking into similar networks from the far-left.

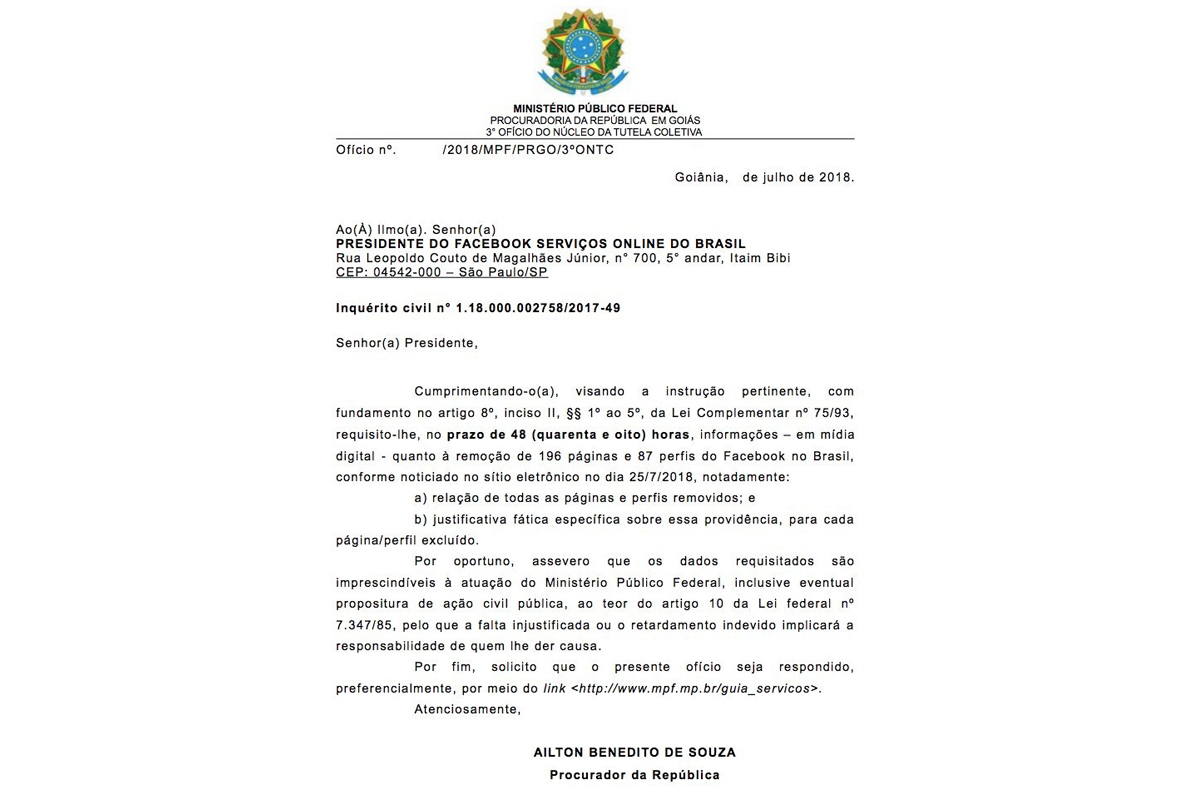

In response to Facebook’s removal of right-wing pages and accounts, the Brazilian Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) issued a statement in which it demanded the company identify specifically which were affected and why. Facebook had 48 hours to reply as of Wednesday, according to the statement.

Facebook didn’t clarify to Poynter whether or not it would respond to the statement, but a spokesperson said Facebook hadn’t been served with any legally compelling order.

The events come amid a period of heightened tension in Brazil over misinformation on Facebook.

In May, the platform expanded its fact-checking program to Brazil with the inclusion of fact-checking projects Aos Fatos and Agência Lupa. Per the program, fact-checkers can debunk fake news on Facebook, decreasing its future reach in News Feed by up to 80 percent. (Disclosure: Being a signatory of the International Fact-Checking Network’s code of principles is a necessary condition for joining the project.)

After joining the project, both Aos Fatos and Agência Lupa received substantial harassment online. Partisan trolls called them censors and leftists trying to push their own agenda, and fact-checkers received personal attacks and threats.

“We got a lot of people visiting our personal social media accounts and some people started printing stuff that we’d published before,” said Cristina Tardáguila, director of Agência Lupa, prior to this week’s protests. “It was kind of hard because we were not expecting that kind of reaction. The first thing we did was we shut our social networks.”

Thursday’s protests in São Paulo continued some of those attacks, calling out fact-checkers in a viral video. About half an hour into the video, one speaker mentions Aos Fatos, Agência Lupa and the IFCN by name and claims that all three are biased censors.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the continent, Tardáguila noticed the pushback from a hotel in Colombia, where she’s supposed to be on vacation for 12 days before elections start.

“I was just going through the Twitter and it’s crazy,” she told Poynter in a voice message. “People again are calling us censors and it feels terrible, actually. They are connecting the third-party fact-checking project to this taking down movement by Facebook and there is no relation at all. Our work has nothing to do with this decision Facebook has taken.”

Meanwhile, Facebook is stepping up its misinformation detection efforts, according to Wednesday’s blog post.

“We now have about 15,000 people working on security and content review across the world, and we’ll expand those teams to more than 20,000 by the end of this year,” it reads. “We use reports from our community and technology like machine learning and artificial intelligence to detect bad behavior and take action more quickly.”