The proverb says that April showers bring May flowers. T.S. Eliot preferred the darker side, proclaiming that April was the “cruelest month.” For journalists, April showers can also bring Pulitzer Prizes.

This April also marks an important historical anniversary: It has been 50 years since the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., on April 4, 1968.

It is also now 50 years since the publication of a famous photograph showing the grieving widow of the fallen martyr. Coretta Scott King mourns at the funeral of her husband, her little daughter Bernice resting her head upon her mother’s lap.

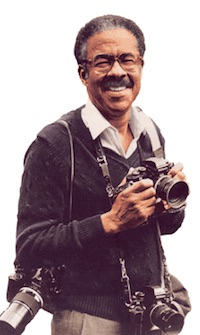

That iconic black and white image of the veiled widow was taken by a man named Moneta Sleet Jr. (For the record he used a Nikon camera with a 35 mm lens, with Kodak Tri-x film.) The following year, 1969, Sleet received news that he had been awarded a Pulitzer Prize. At that moment, Sleet became the first black man to win a Pulitzer, and the first African-American journalist to win one as an individual, rather than as part of a journalism team.

(The poet Gwendolyn Brooks won a prize in 1950.)

It was in 1947, remember, that Jackie Robinson (whom Sleet photographed) broke the color line in baseball. It took another 22 years before a black man crossed that line in the Pulitzer competition.

From 1955 until his death in 1996, Sleet worked for the Johnson Publishing Co. His images, especially in Jet and Ebony magazines, documented every step of the civil rights movement. Beyond that, he captured the work and achievements of black celebrities, performers and politicians in every corner of the country — but also in Africa and around the globe.

Sleet’s eyes were not on a Pulitzer Prize, but on a higher calling: to document the life and times of a marginalized and persecuted people in all aspects of their lives, through triumphs, troubles and tragedies.

The historical collection "The Pulitzer Prize Photographs" describes Sleet’s most famous image and how it came to be captured on April 9, 1968:

It has been just five days since a sniper’s bullet killed the civil rights leader. Coretta Scott King has discovered that the pool of journalists covering her husband’s funeral does not include a black photographer. She sends word: If Moneta Sleet is not allowed into the church, there will be no photographers.

In a Johnson Publishing collection of Sleet’s work titled Special Moments, Sleet offers his own, more modest version of events:

There was complete pandemonium. Nothing was yet organized because the people from SCLC were still in a state of shock. We had the world press descending upon Atlanta, plus the FBI, who were investigating the assassination.

We were trying to get an arrangement to shoot in the church. They were going to pool it. Normally, the pool meant news services: Life, Time and Newsweek. When the pool was selected, there were no Black photographers from the Black media on it. Lerone Bennett and I got in touch with Mrs. King through Andy Young. She said if somebody from Johnson Publishing is not on the pool, there will be no pool.

We … made arrangement with AP that they would process the black and white film immediately after the service and put it on the wire. Later, I found out which shot they sent out. … The day of the funeral, Bob Johnson, the Executive Editor of Jet, had gotten to the church and he beckoned for me and said, “There’s a spot right here.” It was a wonderful spot.

What I noticed … this was prior to the funeral — was the little girl fidgeting there on her mother’s lap. I could relate to that, being a father and having a child close to the same age. Mrs. King was sitting there, stoic and stately, but it was specifically the child who I was thinking about at the time.

In a profession whose practitioners are expected to bring a certain detachment to their work, Sleet saw no reason to apologize for his commitment to the cause of racial equality or for his emotional involvement with those he photographed.

“I wasn’t there as an objective reporter,” he once said. “I had something to say and was trying to show one side of it. We didn’t have any problems finding the other side.” The side of racism and intolerance.

At the same time, his professional standards gave him the foundation to create his best work. He said of covering the King funeral: “Professionally I was doing what I had been trained to do, and I was glad of that because I was very involved emotionally. If I hadn’t been there working, I would have been off crying like everybody else.”

In the Johnson collection of his work, there is a beautiful photo of Sleet and his family. They are beaming. His daughter sits on the floor holding telegrams of congratulations. Sleet is holding his Pulitzer Prize. This is from the May 22, 1969, edition of Jet Magazine:

“You must be joking” were the words Moneta Sleet uttered when informed that he had won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize in news feature photography. “I knew that it was a good photograph, but I knew there were lots of good photographs in the running. So, there’s no need of my lying, I was quite happy to win the award. And my wife, Juanita, and the kids, Michael, Gregory and Lisa, were thrilled.”

At the time, magazine features were not eligible for Pulitzer Prizes. Sleet’s image became eligible because of its distribution by the Associated Press.

The Rev. Kenny Irby, a veteran photojournalism leader and a former faculty member at the Poynter Institute, knew Sleet and looked up to him as a role model and mentor. Via email, he responded to questions about Sleet and his legacy:

As an African-American, a photojournalist, a pastor, and a father, what do you see when you look at the famous photo taken by Moneta Sleet?

Irby: I see great pain and promise in this photograph. Moneta gave me a copy in 1996 after the Olympic Games, which was his last major assignment. For me, it’s the obvious pain for the murdered martyr for justice and peace. I see the promise in his daughter Bernice, who would pick up the baton of her father's work. And I see the promise affirmed by Moneta's Pulitzer Prize, an honor which paved a path for me and generations of other photojournalists.

This is a black and white photograph. What do you see technically that interests you?

Irby: The elegance of the black and white composition has long transfixed me. I love the stark white dress of Bernice, juxtaposed against the black dress and glove. Then there are shimmering shades of gray that flow from the veil throughout the photograph. Yet, the sadness of the eyes in the photograph says all that needs to be said.

Access is so important to any successful photojournalist. What did it take for a Black photographer in the 1960s to get access to important social and political events?

Irby: That's a really great question. It took courage and connections. It was actually Coretta who took the bold stand and insisted that Moneta would be the pool photographer while there was one other photographer inside. Flip Schulke, who was white, also had a relationship with Dr. King.

For Jet and Ebony magazines, Sleet covered the civil rights movement, issues related to Africa, the Black social and celebrity scene. How would you summarize his contribution to journalism?

Irby: Simply put, he was one of the trail-blazers — a tremendously kind human being, a great journalist and nurturing mentor to many.