The European Union's efforts to fight against online misinformation have come up against legal action.

Last week, three media sites in The Netherlands filed a lawsuit against an EU project aimed at curbing online misinformation. The suit claims that EUvsDisinfo erroneously labeled the publishers as “disinforming outlets” on its website, and that the project should remove those accusations from all of their publications and publish a correction, under penalty of a €20,000 fine per day the content remains online.

First reported in Lead Stories, a debunking site run by Maarten Schenk in Belgium, the suit’s plaintiffs include Dutch blogs GeenStijl.nl and TPO.nl, as well as the publisher of De Gelderlander, a regional newspaper.

“De Gelderlander is just a normal mainstream regional newspaper owned by a larger publishing organization,” Schenk told Poynter in a message. “GeenStijl is somewhat of a special case … They have a unique sarcastic style and a fanatical community of commenters.”

That site is also fairly right-leaning, anti-EU and pro-Brexit. TPO.nl is an independent news website and, while the smallest of the three, comparable to GeenStijl, Schenk said.

EUvsDisinfo flagged all three publications for negative stories published about Ukraine. As of publication, all except De Gelderlander’s story had been removed from the project’s database — GeenStijl’s reportedly because of a translation error.

Run by the European External Access Service, the project began in 2015 and describes itself as “part of a campaign to better forecast, address and respond to pro-Kremlin disinformation.” It maintains a database of more than 3,500 “disinformation cases,” ranging from blatantly false propaganda to seemingly anything published by Russia Today. EEAS is the de facto foreign service for the EU and is obviously a key player in negotiations over the Ukrainian conflict.

In each of the cases highlighted in the lawsuit, EUvsDisinfo didn’t label disinformation at all, the plaintiffs argue. It went after news and commentary it didn’t like.

“The EU Taskforce is attacking its ‘own’ European media outlets, and it wrongly labels them ‘fake news outlets,’” plaintiffs wrote in a Feb. 19 writ of summons.

Poynter reached out to EUvsDisinfo directly via email and received a response from EEAS East StratCom deferring any comment to EU spokespeople.

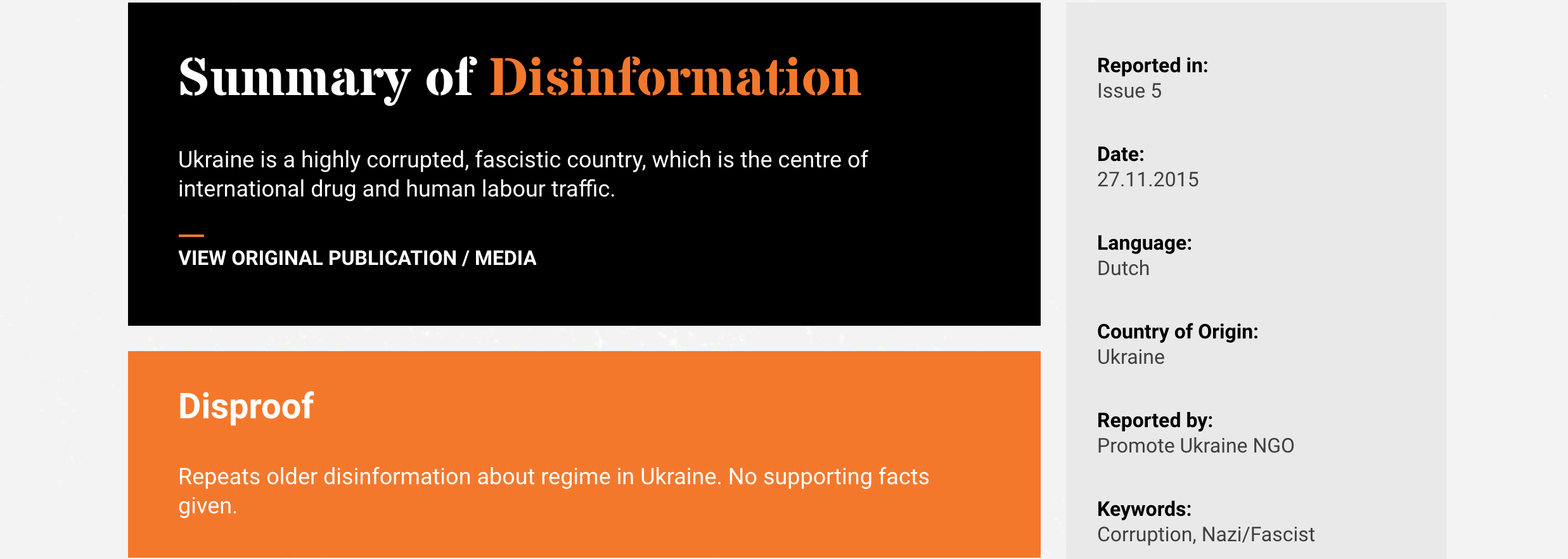

In the case of GeenStijl, the EU’s “disproof” of the claim (“Ukraine is a highly corrupted, fascistic country, which is the centre of international drug and human labour traffic”) was: “Repeats older disinformation about regime in Ukraine. No supporting facts given.” But that oversimplifies the article, which contained links to other sources that had questioned Ukraine in the past, and neglected to note the ironic tone that characterizes GeenStijl, according to the writ.

That same logic seems to have been applied to both De Gelderlander (“The outlet uncritically reports the disinformation pushed by pro-Kremlin outlets”) and TPO.nl (“The article seems to be aimed only at worsening the image of Ukraine …”), the plaintiffs argue. In the former case, the newspaper was simply reporting what was said in a press conference, and in the latter, the site was covering opinions expressed by other sources.

“In short, media which (in the opinion of the EU Taskforce) ‘are only trying to damage the Ukraine’s reputation’ are guilty of spreading fake news,” plaintiffs wrote in the writ. “Apparently, the media are not supposed to spread any reports that could damage the Ukraine’s reputation, especially when the interests of the EU (the treaty) are at stake.”

When asked for comment, an EU spokesperson told Poynter in an email that — while they don’t comment on ongoing legal cases — every piece of disinformation in the database is reviewed by a team that uses a built-in, public-facing reporting system to correct occasional mistakes.

“The Disinformation Review is intended to raise awareness of disinformation and fake news,” the spokesperson said. “It is in no way prescriptive of how the analysis should be used or treated by users, but can provide valuable data for analysts, journalists and officials dealing with this issue, as well as for interested members of the public. The EUvsDisinfo website does not seek to challenge, restrict or interfere with the right of the media to publish differing opinions or viewpoints.”

Poynter reached out to Madeleine de Cock Buning, chair of the Dutch Media Authority, for a comment on the matter, but she declined to comment while it is under adjudication.

On Feb. 2, after receiving a complaint from GeenStijl about the article in question, EEAS said they would discontinue their label of “disinforming outlet” in favor of “outlet[s] where the disinformation appeared,” according to both the writ and an EU spokesperson. However, Peter Burger, coordinator of Nieuwscheckers and an assistant professor at Leiden University, told Poynter in a message that, rather than backing off the project altogether, the EU seems to be reinvesting in EUvsDisinfo.

“Dutch interior minister Kajsa Ollongren has tried to become (the) owner of the fake news issue,” he said. “When the EUvsDisinfo scandal broke, she proposed strengthening the organization rather than disbanding it.”

The kerfuffle, which will go to trial in Amsterdam March 14, is an example of how state-led efforts to counter online misinformation often end up in politicized controversy. In Italy, the recent creation of an online portal where citizens can report fake news to the police received widespread criticism from journalists, while similar efforts in the United Kingdom and France have also attracted ire. Even student-led projects to catalogue mistruths have backfired.

In EUvsDisinfo’s case, Burger said the tendency to label anything remotely pro-Kremlin as disinformation is damaging to everyday journalism.

“The very fact of a news medium quoting this man without noting that his claims were false, is everyday journalistic procedure (although a fact-checker would probably disagree),” he said of the Der Gelderlander story in question. “For EUvsDisinfo, it equals spreading disinformation.”

He broke the issue down into two camps. On one side, disinformation watchers tend to exaggerate the scale and influence of Russian operatives and neglect the potential adverse effects legislation could have on free speech. On the other, free speech advocates are largely unaware of the evidence for real-life Russian disinformation campaigns.

EUvsDisinfo is a case of the former, Burger said.

“I think it was the wrong decision to place this kind of research and outreach with the EU. It’s much too close to the policymakers to come across as independent,” he said. “We should be prepared for disinformation campaigns … so we need disinformation watchers to inform the public, preferably independent from — but, if necessary, funded by — governments.”