In 2016, the editor of a debunking organization wanted to give people a way to submit and check questionable news on the internet.

"From the beginning of Teyit.org, we have collected all data which circulates on our networks," said Mehmet Atakan Foça, editor-in-chief of the Turkish debunking outfit, in a message to Poynter. "We aim to create baseline data to understand what should Teyit.org change."

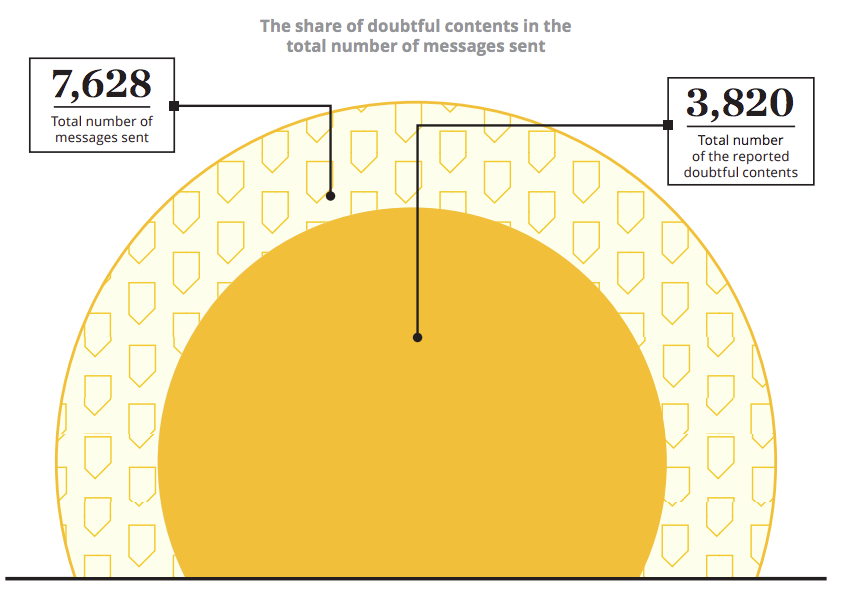

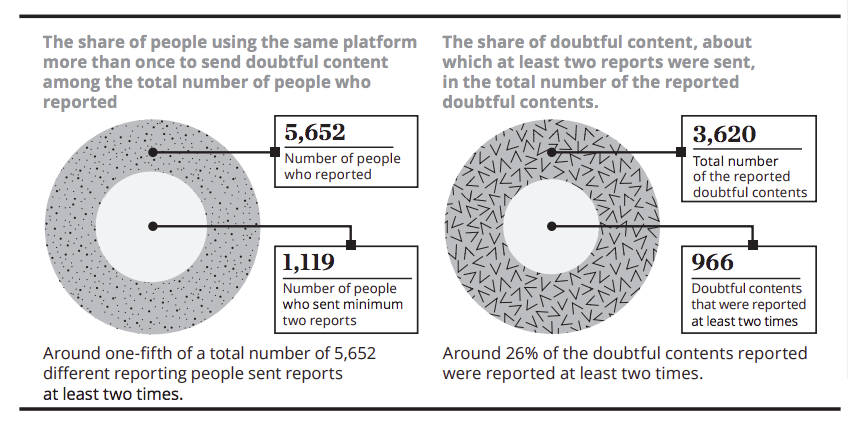

Since then, Ankara-based Teyit has received 7,628 messages from 5,652 people on all social media platforms. And those requests for fact checks now form the backbone of a new report on what Teyit’s audience is most doubtful about.

Published in English on Thursday, the Turkish debunker’s first report is full of insights for civil society organizations and media outlets dealing with misinformation. Among its key findings was the fact that the majority of the organization’s messages were sent via mention or direct message on Twitter and contained political images — a trend that was exacerbated by big news events and crises.

"It was hard to find enough resources and research on habits and behaviors of social media users and news consumers in Turkey," Foça said. "With this report, we will able to see what we could possibly change in the next few years. We would like to trigger a habit of 'doubt before share' for users."

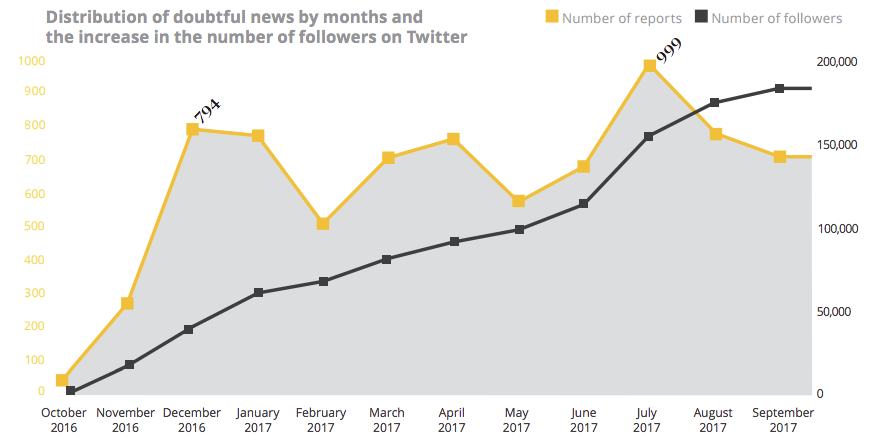

Teyit editors sifted through user messages, which came from Facebook Messenger, Twitter mentions and direct messages, email and WhatsApp, using a prioritization filter with three different components: urgency, virality and significance. They found that fact check requests peaked in December 2016 as a result of a series of terrorist attacks, and again in July 2017 on the anniversary of a botched coup. That date also coincided with viral claims about Syrians, according to the report.

These peaks seem particularly relevant seeing as Teyit also grew its social media following significantly since its founding in October 2016.

The most reported content of the year was a video from December 2016 that purported to show the Islamic State burning two Turkish soldiers alive. Teyit didn’t fact-check that story, but it did appear in Al Jazeera.

Other popular fact check requests included photos from August 2017 purporting to show the violence against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, as well as an April 2017 video that claimed to depict a “Yes” vote in a school during the Turkish constitutional referendum. The latter was not published due to insufficient evidence.

More than a fourth of the doubtful content Teyit received was reported at least twice, suggesting that a good chunk of the organization’s users were confused by the same misinformation online.

Teyit fact-checked more than 16 percent of the reports that it received on its website. The rest were not due to a lack of information about the claims in question.

Aside from the fact that most of the messages sent to Teyit were political, perhaps the most interesting finding in the report has to do with the specific media in question. More than 42 percent of the doubtful content sent to Teyit came in the form of images, particularly memes and screenshots. This is likely due to the fact that images can go viral quickly by eliciting strong emotional responses, according to the report.

Taken together, those findings present a clear view of what Turkish social media users are doubtful about — and what other fact-checking organizations could learn from them. Broadly speaking, demand for verified information increases during times of crisis, and fact-checkers would do well to capitalize on that demand.

Read Teyit’s report in full here.