Grace Xu doesn’t make any money fact-checking. She’s not a journalist and she has a day job as a computer scientist in the San Francisco Bay Area.

But she helped launch one of the few debunking operations on WeChat, a private messaging application that’s extremely popular in China and among Chinese expats.

“You don’t have to be a professional to tell others what is true and what is not true,” she said. “And with the Chinese online community, the problem is that a lot of people don’t read English news. They just read whatever accounts send them.”

Roughly translated as “No Melon” — a play on Chinese web slang about how much users care about certain posts — the fact-checking project started up immediately following the 2016 U.S. presidential election and lives on WeChat (The platform didn’t allow external links until recently). Xu said she was inspired to create the channel with some of her friends after watching a barrage of political misinformation get shared among Chinese-Americans on WeChat.

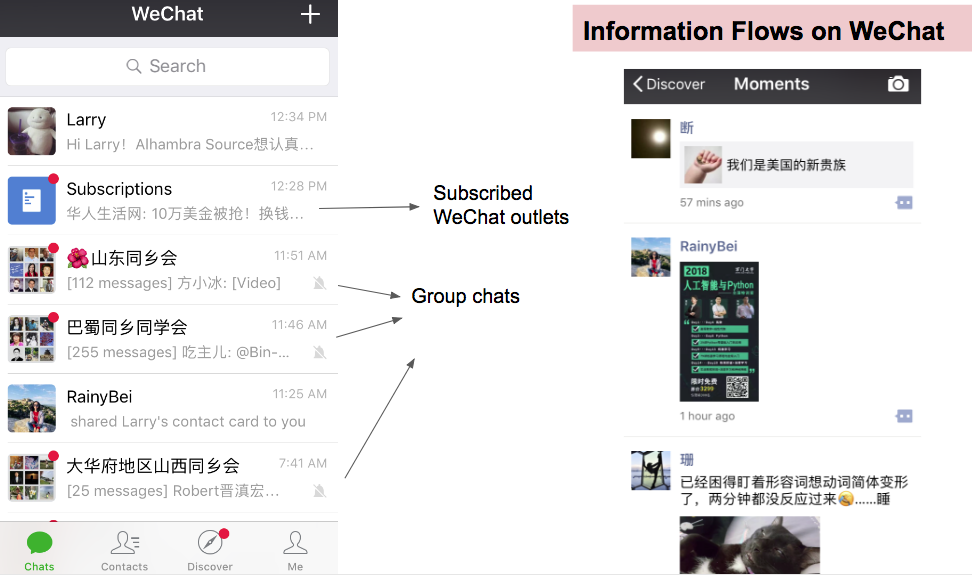

Now, while they publish on and off depending on their different work schedules, the group amasses anywhere between 2,000 and 10,000 views per post. That’s because, like WhatsApp, friends often forward each other articles they see on in groups on the platform, where No Melon’s writers post their work.

“We only have 20 percent of views on articles from subscribers — 80 percent are mostly from people who didn’t subscribe but saw the article in their friend’s circle,” Xu said. No Melon receives an average of $40 for click-throughs per post. “We’re not making a living out of this.”

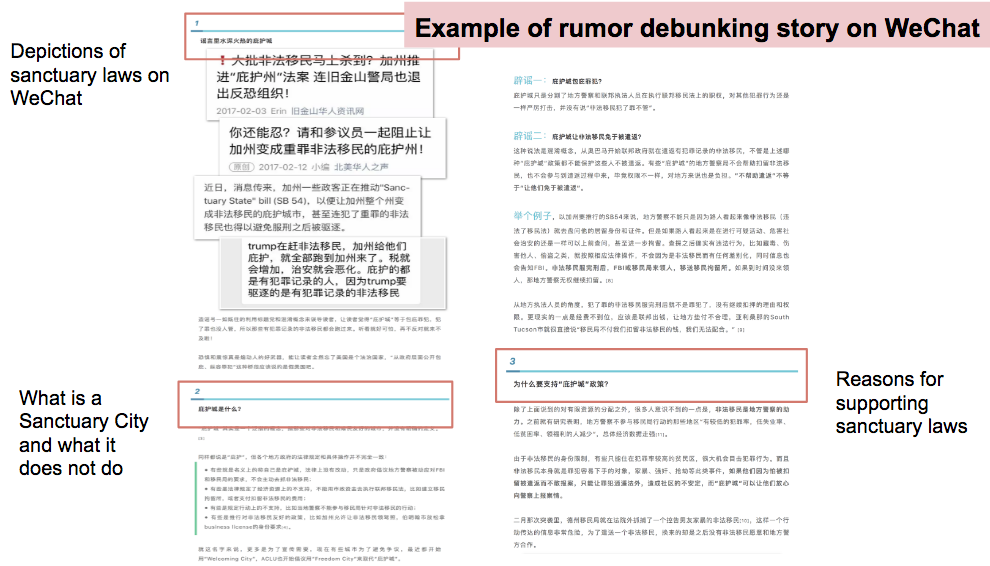

No Melon is a small example of a handful of “guerrilla” debunking projects on WeChat, which has about 1 billion monthly active users worldwide. Another, the Center Against Overseas False Rumors’ Anti-Rumor project, also started in the aftermath of the 2016 election and has about 22 volunteer writers. It publishes between three and four fact checks per week to a subscriber base of about 10,000 people.

The ad hoc method these projects employ is similar to the approach attempted by fact-checkers on WhatsApp, where readers are asked to send potential hoaxes to institutional accounts and distribute the resulting fact checks. And like WhatsApp, these fact-checkers said their work doesn’t really scale to the spread of misinformation on WeChat.

“I do not think it was effective. The anti-rumor articles spread 100 times slower than rumors,” said Lian Duan, a writer for Anti-Rumor, in an email to Poynter. Sometimes WeChat’s owner itself, Tencent, will re-share the project’s fact checks to its millions of followers, but not often. “That's why we produce much less articles then two years ago.”

But WeChat is a completely different animal than WhatsApp — and its misinformation problem is relatively under-researched compared to platforms like Facebook and Twitter, where viral hoaxes reach mainstream audiences in the U.S. and Europe.

One expert on WeChat misinformation is Chi Zhang, a doctoral candidate at the University of Southern California and a fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism who has extensively researched the topic. She told Poynter the problem is partially created by the lack of objective news on WeChat.

“There’s really no kind of expectation that these (accounts) would be rigorous news reporting,” said Zhang, who discussed the app’s misinformation woes at the International Fact-Checking Network's Global Fact-Checking Summit in Rome last month. “That’s one thing that really makes misinformation proliferate in the space, but also I think it really kind of sets different expectations — and the issue of trust and credibility has a very different playing field in the app.”

In many ways, Zhang said WeChat isn’t at all a messaging app — the platform has a built-in publishing system with as many as 10 million different official accounts distributing content to users. Only a handful of them have corresponding news outfits in the real world, like The New York Times would if it created a WeChat account, and many focus on content aggregation over objective reporting.

That structure has repercussions for how users perceive the news.

“They’re not just memes, they’re not just hyperlinks shared via other websites on the open web — they’re constructed within WeChat itself,” Zhang said. “So essentially WeChat is kind of like Facebook in that people just go straight to the platform for their news. A lot of content providers are supplying that and meeting that demand.”

“They don’t really abide by any journalistic norms.”

The same can be said for the small groups of part-time debunkers who have made a hobby out of fact-checking WeChat rumors. Zhang said many of those groups are run by people without journalism training or a priority for values like objectivity, nonpartisanship and fairness.

“These are also not really journalists — they have full-time jobs, they’re researchers or students or people just doing this as a side gig,” she said. “Objectivity is not their main concern. Sometimes there is subjective evaluation in the piece, saying things like, ‘This is so ridiculous’ … The kinds of conversations are more casual and less focused around hoaxes, but in that way, you build a very engaged group of readers.”

Xu agreed, saying that No Melon — which is also active on Weibo, another popular Chinese social media platform — and other groups are more aimed at keeping people informally informed than abiding by any journalistic principles. She estimated that about 20 percent of what No Melon publishes are opinion articles, with about one-third being fact checks.

“I don’t really describe us as a Snopes or fact-checking site — fact checks are just part of our topics,” she said. “We have more topics that are related to America politics. We just want to keep people well-informed.”

So what creates credibility in that environment? Zhang said it comes down to repetition.

“I’ve heard a lot of people say they don’t even pay attention to what news outlet published the article. It’s like they don’t really trust some outlets more than others,” she said. “Really where credibility comes from is this cumulative repetition and familiarity with a story. If outlets copy from another one and it gets shared around, that’s what creates trust and credibility.”

And that is what often leads to widespread dissemination of false or misleading news stories or memes, which get copied by different accounts 10-20 times and play on users’ emotions to get views. Zhang said misinformation on WeChat must be viewed in two different user contexts: people in mainland China and expats in the U.S. and elsewhere.

She said misinformation among the former group usually takes the form of public safety or health hoaxes, such as hoaxes about certain foods causing cancer. Zhang said those topics often appeal to middle-age users — and there’s no good way for them to disentangle what’s true and false.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., misinformation on WeChat looks pretty similar to what an American might encounter on their Facebook feed: hyperpartisan memes, stories and videos that aim to inflame ideological divisions. Zhang said a lot of the content skews conservative on issues like immigration and affirmative action.

“Those stories are more eye-catching — things like, ‘In California, there’s a new law permitting HIV-positive individuals to donate blood,’” she said. “This is like facing a crowd that is not as politically sensitive or knowledgeable and essentially creating a picture of liberal California being just egregious and ridiculous.”

Xu said another one of the other top hoaxes No Melon has seen go viral is a fake story that claimed there was going to be a national day of violent riots on Nov. 3, 2017. She said the rumor started on 4chan and was spread by the popular WeChat account College Daily, which caters to Chinese foreign exchange students.

“I swear at least 20 percent of my friends in America shared it. We wrote an article on it and got it out before Nov. 3,” Xu said. “People just forgot about it — terror is what draws people attention. They didn’t know they were being used as a medium for drawing more clicks to that platform.”

“This didn’t even make the news in the U.S. I had coworkers and family members in China warning us to be careful.”

Xu estimated that about 60 percent of No Melon’s audience is outside the U.S. — and that’s significant for its Chinese readers.

“In China, you’re kind of isolated — you don’t have access to the NYT or (The Washington Post) and you basically read whatever a popular WeChat account feeds you,” she said. “We want to keep that audience informed as well.”

In the U.S., Zhang said it’s important for news organizations to pay attention to misinformation on WeChat because it’s increasingly a place where political misinformation is affecting the voting preferences of Chinese-Americans. There were about 5 million Chinese living in the U.S. in 2015, according to data from the American FactFinder, and they comprise significant portions of the population in many Southeast Asian countries, Canada, Peru, Russia and Australia.

“In the U.S., I feel there’d be a really great interest for it because a lot of the first-generation Chinese immigrants’ political mobilization is being carried out through WeChat,” she said. “That’s the major space where they get news about U.S. politics.”

Structural and user differences aside, WeChat stands out from other tech platforms in that its parent company, Tencent, has taken some aggressive measures against misinformation.

“WeChat is keenly aware of the problem — it’s kind of hard to miss,” Zhang said. “And from the China side, the Chinese authorities really dislike and frown upon any information that creates what they call social discord or rumors in any form. The company has a strong incentive to rein in some of this misinformation.”

Tencent started its own fact-checking operation, which mainly focuses on debunking health rumors on the platform. Within the app, users can search for and ask questions about rumors — there’s even a game component to it.

In an email to Poynter, Tencent Global Communications Director Portia Huang said that program, in addition to strict content policies and a monthly publication of the top fake news stories on the platform, is the company's primary weapon against misinformation.

"We frequently conduct reviews to ensure platform integrity and will block or suspend official accounts if they are found to be spreading misinformation, hate speech, indecent content or other information prohibited on our platform," she said. "In addition, we work with credible organizations to help correct misinformation, and we launched the 'Rumor Filter' official account in 2016 and the 'Rumor Filter Assistant' mini-program in 2017 to help users verify the veracity of dubious news reports and notify users if any news reports they read or shared contain misinformation."

At the same time, Zhang said political fact-checking doesn’t exist in China because government censors already target those kinds of rumors online. That gives Tencent itself some leeway when censoring what gets posted on the app — it regularly takes down rumors and hoaxes that get wide reach.

In countries like the U.S., that’s less common, and political misinformation frequently takes off as a result. Xu said Chinese immigrants frequently turn to WeChat as a key source of news, and the fact that American institutions aren’t paying enough attention to the platform is troubling.

“You have some immigrants who want to be part of an American community — they make friends, speak fluent English, read things online in English,” she said. “But you also get this slightly older Chinese generation. They might work for an American company, but their social life is in the Chinese community. Certainly, they’re low-informed, but they’re well-educated.”

“Chinese-Americans are one silent group and they’re being ignored.”

As for potential solutions, Zhang said brand recognition would be a major obstacle for those trying to debunk misinformation on WeChat, since average users don’t seem to care about who’s publishing what. Xu said she’d like to see WeChat itself start labeling whether or not specific stories have accurate sources.

Then there’s what researchers like Zhang don’t yet know about misinformation on WeChat, such as who’s behind some of the most wide-reaching — and growing — hyperpartisan and fake news outlets, as well as how many of those outlets are exclusively profit-driven by advertising.

Ultimately, Zhang said that several different stakeholders need to tackle misinformation on WeChat together in order to effectively combat it.

“It needs to be a concerted effort — whether it be community organizations or local media outlets or political parties that have an interest in reaching these constituents,” she said. “It’s a really effective tool — even though there’s a lot of misinformation, on the other hand, you can use it to reach the right audiences. I think a big step is for these key players to realize that WeChat is a valuable tool.”