One flooded house on the San Jacinto River in Kingwood, Texas might well be the poster child for what's wrong with the National Flood Insurance Program. Houston Chronicle reporter Mark Collette found that one home, "has had 22 flood insurance claims totaling more than $2.5 million since 1979. That's at least eight times what the house is worth." That is just one example of tens of thousands around America. By one estimate, between 1978 and 2015, the NFIP paid $5.5 billion to repair and rebuild more than 30,000 “severe repetitive loss properties.” FEMA says up to 20 percent of flood insurance payments go to less than two percent of homes. The same homes flood year after year and the owners collect the payments, rebuild and repair and wait for the next flood.

Collette reported that this same fix-it-up and flood-it-again cycle happened around the country and it is bankrupting the flood insurance program that comes up for reauthorization in a few weeks. The flood insurance program is more than $25 billion in debt and Congress is considering some changes in the program, but as Collette reports, the changes do not tighten the requirements that when 50 percent of a property is damaged by flood, the property should be elevated or demolished.

Of 36,000 records of "severe repetitive properties" the Chronicle examined, 16 percent showed evidence that they had been damaged "beyond the 50 percent threshold."

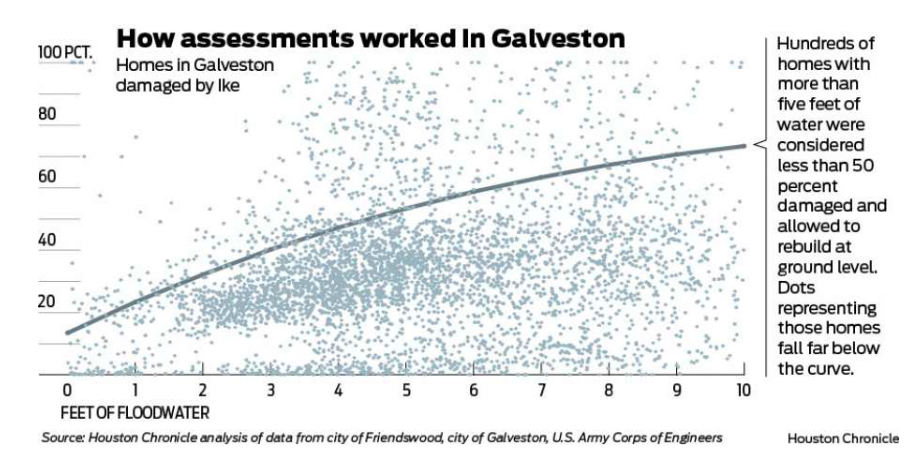

The flood-fix cycle could end if local inspectors acted more forcefully. The Chronicle story said Galveston homeowners who owned flooded homes 300 feet from the beach saw water destroy two-thirds of their homes' value but local inspectors called it a 44 percent loss which allows the homeowners to fix the damage without elevating the property to prevent further losses. The story said political considerations overwhelm clear-minded calculations and local government is reluctant to tell homeowners who have suffered a big loss that they will lose even more money, so they allow them to repair and rebuild.

Get local

Collette posted the data he collected for other journalists to examine and use.

"It is our cleaned up data," he said.

He restructured the complex data that FEMA provided and he attached a "data dictionary" to help you understand how he made decisions.

"There is a lot that can be done with this data, I do encourage people to run those same analyses at a local level, especially in places like Louisana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, the Eastern Seaboard where Hurricane Sandy hit."

The data shows repetitive flood claims on houses in places you might not expect including Missouri, Connecticut, Washington, New York, New Jersey and both North and South Carolina.

As you look at the data, you will see what experts have said for years, most repetitive flooding is not from hurricanes and tropical storms.

"It is mostly river flooding and places away from the coast that tend to have a lot of repetitive floods," Collette told me. "Hurricanes are relatively rare compared to a place on the river that might have the river rise up every few years."

Terms to understand

FEMA has specific terms that journalists need to understand to tackle this story:

A repetitive loss property is a property for which two or more flood insurance claims of more than $1,000 have been paid by the NFIP within any 10-year period since 1978.

A severe repetitive loss property, as defined by Congress in the Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2004, is a 1–4 family property that has had four or more claims of more than $5,000 or two to three claims that cumulatively exceed the building’s value. For the CRS, non-residential buildings that meet those same criteria are also considered severe repetitive loss properties.

A repetitive loss area is a portion (or portions) of a community that includes buildings on FEMA’s list of repetitive losses and also any nearby properties that are subject to the same or similar flooding conditions.

Fight for the data

FEMA, which oversees the flood insurance program, does track homes with "repetitive losses," but it does not make it easy to identify them. The Chronicle said:

Because of restrictions under the federal Privacy Act, the agency does not release a full set of insurance claims data under the flood insurance program. The database it did provide contains data for more than 36,000 buildings identified as severe repetitive loss properties as of January 2018. Those are defined as having filed multiple claims for damages above a FEMA-set threshold. The database provides a unique property number, city and zip code, but does not identify addresses or owners.

Think about that for a moment.

Even though the flood program is run by the federal government, the specific claims data is not an open record.

"I was dismayed by that but not surprised," Collette said. "It is not a claim with a private insurance company and I think those things should be public for sure. This was the single biggest obstacle for this project."

The specific data exists on the local level, too. For example, The City of Houston collects damage assessments data and that is separate from the insurance adjuster data, which is private. But even after the Chronicle asked the state Attorney General to force the city to release the data, the state denied the request. At the same time, the City of Galveston did release the specific data and The Chronicle was able to use it to build a map showing the homes that were more than 50 percent damaged but still rebuilt.

Not only would journalists want to know this data, but imagine you were a home buyer and wanted to know the flood claim history on a house.

Collett told me, "There are two components – the flood insurance component – if you go out and get the policy FEMA has to tell you the loss history on that property. But if there was a loss and the person did not file a claim or didn't have insurance and lots of flood-damaged houses don't have insurance, it will not show up on the list."

But he added, there are also state and local requirements to disclose a property's flood history "to the best of the seller's knowledge."

Depending on the state or city, that enforcement can be lax. In other places, the loss history may be attached to the property deed so the history is documented.

Collette told me, "Besides making it impossible for the taxpayers to figure out what they're paying for, it also creates another fundamental problem: Figuring out what flooded and what didn't. That's not only important for prospective property buyers. It's also important from the standpoint of managing the floodplain. Are we prioritizing drainage projects well? Are low-income people and people of color getting short shrift on buyouts and flood control while white and affluent parts of town get bailed out? And what do we stand to lose in the next flood? We can't answer these questions if the government keeps a padlock on our information."

The National Resources Defense Council says even when federal flood insurance payments go toward elevating damaged homes on pilings or raising their foundations, "increased elevation may end up being only a temporary fix, particularly as sea levels rise in coastal areas and larger floods become increasingly likely along inland rivers."

Eighty-one percent of flood-damaged damaged buildings are single-family homes, and NRDC says, these properties routinely flood every two to three years and have been rebuilt an average of five times.

NRDC says, "Among severe repetitive loss properties, less valuable homes were more likely to suffer flood damages that exceeded the property’s value. Among single-family homes worth less than $250,000, the average sum of all damages ($133,923) exceeded the value of the average home ($109,882). Among single-family homes worth more than $250,000, however, average damages were some $200,000 less than the average home’s value."

Does your community "have a plan?"

Collett said one way for local reporters to attack this story is to ask local officials if they have a plan to deal with catastrophic floods.

"If you are in a community that does not have a plan in place for what to do when the big storm comes and you suddenly have to enforce these rules communitywide, that is when the big mistakes are made," he said. "That is when it is hard to hold the line."

If local leaders make it clear before they face a flood that they will enforce FEMA flood standards and will not issue construction permits to homes that are heavily damaged, then there is less pressure to enforce the rules when the water rises. Collett says FEMA does have a rating system that applies discounts to communities that have a good floodplain management programs. But he says, "if you don't follow the requirements, communities could lose their ratings, but it almost never happens."

The Natural Resources Defense Council says this issue could become even more important in the future as climate change increases flood risks.

One place journalists can turn to for expertise on repetitive flood is The Association of State Floodplain Managers. The group keeps a state and local contacts page that will help you zero in on stories near you. It also keeps a lot of easy to access data on the site.