Eighty-nine years ago to the day, at 10:30 a.m. on Feb.14,1929, four men associated with Al Capone fired 70 rounds from Thompson machine guns (known as Tommy Guns) and killed seven rival gang members.

Witnesses said some of the shooters were dressed as cops.

Nobody was ever prosecuted for the crime.

In that one year, Chicago counted 16 gang-style killings. The year's murder toll climbed to a breath-taking level, 64 deaths.

It was a spike in the crime rate that journalists and politicians latched on to.

In his excellent Nat Geo story on the history of how mob violence led to gun control, Gabe Bullard writes:

“Why should desperadoes, brazen outlaws of the period, be permitted to purchase these weapons of destruction?” wrote the editors of the Waco News-Tribune in 1933 after the Texas — yes, Texas — statehouse passed a ban on fully automatic weapons.

When New York state banned submachine guns, the Ironwood Daily Globe in Ironwood, Michigan, called it a “a very excellent law” and went on to say, “It is hard to think of any good reason why every other state in the union should not copy it at once.”

Here is a snippet of a 1934 Chicago Tribune editorial that ran in 1934. You could copy and paste it today and still be relevant:

It is notorious that when restrictions are put upon the possession of firearms or any particular kind of weapon they never are effective against the criminal classes but only put the peaceable man at a disadvantage or in a false position before the law. The prohibition does not bother the enemy of society but it makes a technical offender of the decent citizen. The man who would not misuse a weapon is the man who is injured. The drive for public security is thus given the wrong direction.

President-elect Herbert Hoover had promised to get control of crime. He saw the St. Valentine's Day killings as a platform to launch a plan. But a stock market crash took the national attention other places.

At that time, gun regulations were largely state and local matters, but the St. Valentine's Day killings touched a nerve. A 2012 article by Whet Moser for Chicago Magazine includes a quote from a gun runner from the gangland killing era of 1929.

“It is no trouble to buy machine guns,” Daniels told a reporter. “All I had to do was to send to New York for them and they were shipped to me. I was getting them for the Mexican rebel army.”

President Franklin Roosevelt saw a need for the federal government to step in because the gun trafficking was crossing state lines. Illinois was trying to do something about the machine-gun killings, but as long as guns were so easy to buy elsewhere, local regulation was futile. So along with his New Deal programs that created jobs and built dams, Roosevelt launched "A New Deal for Crime," which included The National Firearms Act of 1934.

Roosevelt wanted to tax all guns and create a national registry for guns. That idea was about as popular then as it is now. Then, as now, the cry arose that the Second Amendment protected gun ownership. But then, as now, the Supreme Court recognized that with every right comes individual responsibility. Free speech is not unlimited and neither is gun ownership.

In 1934, the National Firearms Act didn't ban machine-guns, but it heavily taxed and regulated them. That regulation stands today. Then Congress passed the Firearm Owners' Protection Act of 1986, which bans the sale of "new" fully automatic weapons, which is why fully automatic guns today are older weapons.

To own a fully automatic weapon, a machine gun, the owner must obtain a federal ATF stamp, undergo an extensive background check and even notify local authorities that they own such a weapon. In the more than four decades that I have been a journalist, I have never covered or heard of a murder in the U.S. in which the shooter fired a registered fully automatic weapon. Mother Jones magazine has cataloged shootings going back to 1982, and not one involved the use of a fully automatic machine gun.

How the deaths of JFK, RFK and Dr. King and shooting of President Reagan shaped gun laws

For decades, long after the Firearms Act of 1934, Americans have turned to legislation as a response to an incidence of gun violence.

After Lee Harvey Oswald shot President John Kennedy, a new president, Lyndon Johnson, included a gun control measure in his Great Society proposal as a response to the nation's mourning.

Two more high profile deaths passed before, in 1968, Congress responded with The Gun Control Act of 1968. The 1968 law made it illegal for felons to possess a gun. It required gun retailers to keep records of gun sales but did not require them to report those sales to local or federal government.

For gun control advocates, the fact that there was no federal gun registry was a deep failure, just as it was for FDR. The 1968 act also tried to stop the flow of cheap pistols called "Saturday Night Specials" but did nothing to regulate rifles and shotguns, even though both JFK and Dr. Martin Luther King were killed by rifle fire.

After a lone gunman with a pistol shot President Ronald Reagan and his press secretary, James Brady, Congress acted again, this time passing the so-called "Brady Bill," which placed a waiting period on retail handgun sales and required a background check for the retail purchase of weapons.

In 1989, a mass shooting in Stockton, California, that killed five children and wounded 30 teachers and students ignited a conversation about limiting more than handguns. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed a ban on assault weapon sales. It applied to weapons such as the AR-15 used in Wednesday's school shooting.

The assault weapons ban of 1994 applied to weapons manufactured after the date of the ban's enactment, and it expired in 2004. After the assault weapons ban expired, the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle became a wildly popular weapon among sports shooters. Less than 24 hours after the Parkland, Florida, school shooting, the drumbeat began to reconsider re-instating the ban.

The lessons

In the past 24 hours, America once again is talking about what, if anything, the nation could or should do to stop the carousel of gun violence. America has had the same conversation with itself for nearly a century. The response has two common ingredients; the watered-down solutions produce watered-down results and when it comes to gun laws, America responds to tragedy and outrage.

America also has the complexity of a constitutional protection for gun ownership that has been confirmed by a U.S. Supreme Court multiple times. So even if Congress agreed to ban or restrict some weapons, begin a gun registry or place restrictions on ammo sales, recent court rulings arc toward loosening restrictions, not tightening them.

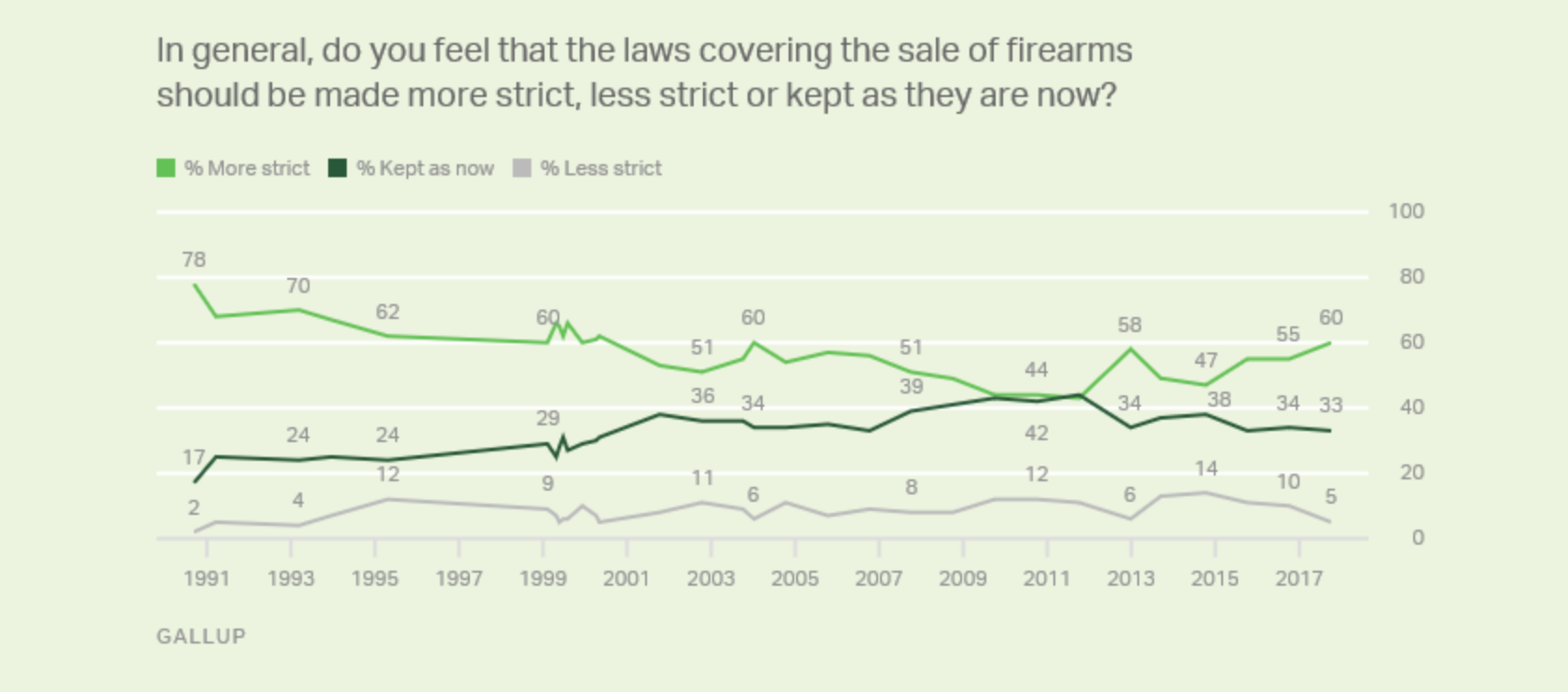

The Gallup polling organization has been tracking American attitudes toward gun ownership since 1960. The highest spikes in those polls occur right around the time that each of the major gun laws took effect since the polling began. And, it is interesting to see that support for additional gun restrictions fell sharply right after the new laws were enacted.